What do Ukraine, Sri Lanka, and Ghana have in common? They’ve all guaranteed bonds that once traded at a sizeable discount to their sovereign counterparts.

In the months since Russia commenced “special military operations” in late February of this year, much of the world has watched Russia’s full-scale invasion of Eastern Ukraine with horror.

As that invasion has dragged on into its fifth month, much attention has been paid by financial markets and the press to the impact of the Russian invasion on Ukraine’s sovereign bonds and GDP warrants.

That scrutiny will doubtlessly intensify in coming months as holders seek to organize in advance of an upcoming $900mm maturity in September. Comparatively less focus has been devoted, however, to Ukraine’s billions of dollars of guaranteed obligations, and to one $700mm Eurobond issuance in particular.

Issued last summer by Ukravtodor, the Ukrainian state road authority, the 6.25% bonds maturing in 2028 are backed in the first instance by tolls, fines, and fees collected by the agency, as well as excise tax revenues allocated by statute to Ukravtodor from the central government.

In addition, the bonds also benefit from a sovereign guarantee; specifically, Ukraine has “irrevocably and unconditionally” guaranteed “the due and punctual payment of all amounts payable” with respect to the Ukravtodor bonds.

The Deed of Guarantee for the bonds describes the guarantee as a “principal obligation” of Ukraine, stating that the sovereign is a primary obligor under the bonds alongside Ukravtodor, and “not merely [a] surety.”

In an enforcement scenario, holders would almost certainly rely on this language to argue that Ukraine’s obligation constitutes an “independent guaranty” under English law—in other words, that it is not necessary to first pursue the issuer before proceeding against the guarantor (similar to a guarantee of payment under U.S. commercial law).

Further, according to the offering documents, the guarantee is pari passu with all other unsubordinated, unsecured indebtedness of Ukraine, meaning that holders would likely argue that any recoveries from Ukraine on account of the guarantee should be at a minimum equal to those received by holders of the government’s sovereign bonds in a restructuring.

Finally, the terms and conditions of the bonds appear to include a cross-default provision with respect to Ukraine’s sovereign debt. That means that, even if Ukravtodor were to remain current on its debt service in spite of a sovereign default, bondholders would argue that such default nonetheless accelerated Ukraine’s obligations under the guarantee, thereby allowing for immediate enforcement thereof.

In sum, if Ukravtodor’s holders were successful in making these arguments, then upon a default by Ukraine on its sovereign debt, those holders could immediately assert a claim against Ukraine in the full amount of the Ukravtodor bonds that remain outstanding, and then proceed against Ukravtodor to collect any remaining deficiency.

In light of the foregoing, one might expect the market to view recoveries on the Ukraine sovereign bonds as a mere floor, to be supplemented by whatever can be recovered directly from Ukravtodor (or, in the alternative, for the Ukravtodor bonds to be carved out from the scope of a restructuring entirely).

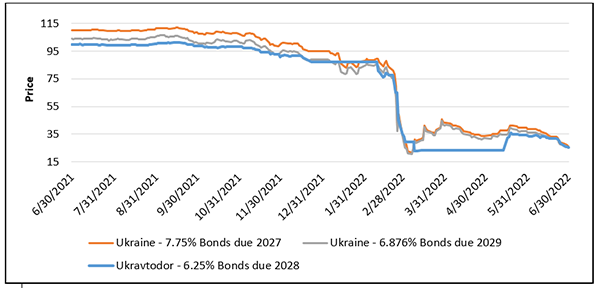

The trading prices for each respective security seems to tell another story. In fact, although prices have recently normalized, the Ukravtodor 6.25% Eurobonds maturing 2028 have historically traded at a significant discount to Ukraine’s sovereign bonds.

Based on available data, as of June 30, 2022, over the prior year the Ukravtodor bonds appear to have traded at an average of nearly 810 basis points less than Ukraine’s 7.75% bonds due 2027.

No doubt the higher coupon and shorter term of the sovereign bond vis-à-vis the guaranteed bonds were relevant to their respective market prices; however, the Ukravtodor debt also lagged approximately 360 bps behind the 6.876% bonds due 2029:

Source: Bloomberg Terminal as of June 30, 2022.

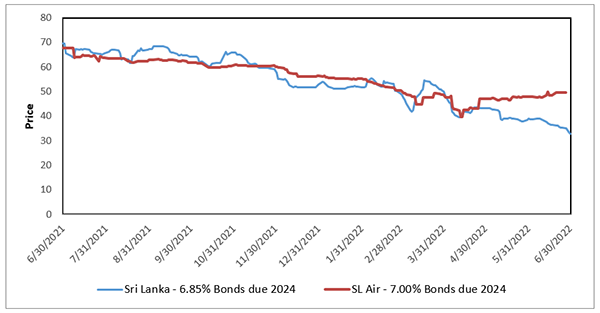

And in case one thought this was a mere fluke, this pattern isn’t limited solely to Ukravtodor. A similar dynamic previously existed in the relative prices of similarly-dated Sri Lankan sovereign debt and bonds issued by Sri Lankan Airlines backed by a sovereign guarantee: again, despite the potential for multiple sources of recovery, the latter traded for much of 2021 and early 2022 at a sizable discount to the former, with the spread at one point reaching nearly 700bps:

Source: Bloomberg Terminal as of June 30, 2022.

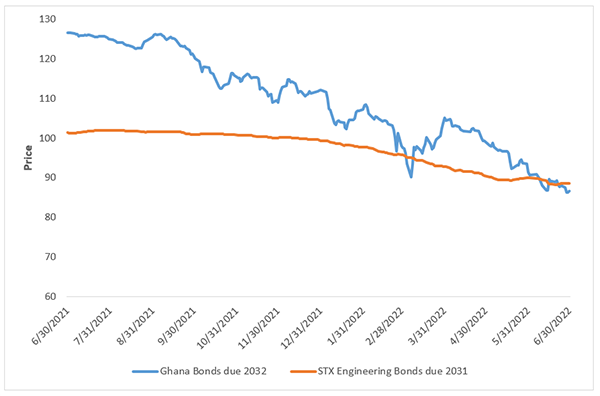

And in the twelve months ending June 30, 2022, bonds issued by STX Engineering and guaranteed by the Ghana central government lagged similarly dated Ghana sovereign bonds by an average of over 1,200 bps:

Source: Bloomberg Terminal as of June 30, 2022.

Historically, the same thing occurred in Puerto Rico in the wake of its default, where, for a time, bonds issued by the Public Buildings Authority that benefited from a central government guarantee traded at a discount to directly issued general obligation bonds.

Those investors shrewd (or perhaps lucky) enough to buy low on PBA bonds were no doubt pleased by the ultimate outcome in that case, where some PBA bonds received recoveries in excess of 10% higher (as a percentage of face value) than similarly dated GO bonds.

Now, as noted, in recent weeks the trading prices of Ukravtodor’s bonds and similarly dated Ukraine sovereign bonds have been rapidly converging. And since a Sri Lankan default became seen by the market as all-but-inevitable in April 2022, the Airlines bonds have now consistently traded above their sovereign counterparts.

Similarly, as Ghana’s sovereign bonds have tumbled in the wake of ratings downgrades, the spread between its direct and guaranteed bonds has all but evaporated as well.

But even if market participants appear to have gotten wise to the arbitrage potential inherent to these specific credits, the question still remains: what causes the seemingly bizarre price dislocations with respect to sovereign guaranteed bonds to arise in the first place?

As noted, this phenomenon is no doubt explained in part by differences in tenor and yield. Variations in legal protections (e.g., choice of law provisions, collective action clauses) should, at least in theory, also impact price.

So too should liquidity play a role, as there is often simply more sovereign debt available to change hands: Ukravtodor’s $700mm issuance, for instance, pales in comparison to the $20bn+ of external sovereign bonds issued by Ukraine that remain outstanding and available to trade. Some have also suggested that psychology plays a role, with certain investors—whether rightly or wrongly—simply viewing a sovereign obligation as “the safest credit.”

Whatever the reason, the fact is that corporate bonds backed by a sovereign guarantee often trade at a relative discount to the sovereign’s “true” credit risk, providing the attentive investor with opportunities to build a position at an attractive price. But, as with most good things in life, those opportunities don’t seem to last too long.