Billions of dollars in dirty money flowed through Danske Bank’s branch in Estonia, an explosive 2014 audit revealed. The original report had never been made public, until now.

Billions of dollars in dirty money flowed through Danske Bank’s branch in Estonia, an explosive 2014 audit revealed. The original report had never been made public, until now.

Key Findings

- The audit report provides an inside look at tactics used to move money around the world without accounting for it — and shows how Danske turned a blind eye to them.

- Danske’s foreign clients frequently transferred huge sums around the world with only the vaguest of explanations.

- Bankers accepted documentation in languages they did not speak and failed to query absurd contracts, including one for a shipment of paint jars worth $1,000 each.

- Other clients listed addresses that did not exist, claimed to be sending massive quantities of goods to the middle of nowhere, and lent each other money on unclear pretexts.

- When one group of clients aroused suspicion for making huge transfers, the bank suggested to them that they leave, to avoid having to report them to authorities.

On a warm Monday morning in June 2014, two auditors from Estonia’s financial regulator stepped into the Tallinn office of Danske Bank, armed with a single piece of graph paper handwritten with the names of 18 of its clients, and demanded to see their records.

At first glance, the customers on the list sounded boring. They were mostly obscure trading companies with generic names like Hilux Services and Polux Management. But the auditors — who had been tipped off by a police unit that tracks financial crime — didn’t have to dig too deep before things got very strange.

The companies were moving huge amounts of money through Danske Bank from Russia, Azerbaijan, and Ukraine, and justifying them with nonsensical contracts.

One company with no website or internet presence, started by a 21-year-old from Azerbaijan, received millions of dollars from Russian state arms company Rosoboronexport for no clear reason.

Another company from Uzbekistan bought $2 million worth of “building materials” from the remote British Virgin Islands. A third company agreed to loan out $150 million, but inexplicably transferred $582 million instead.

After more than a month poring over Danske’s books, the auditors produced a damning report about the bank’s failure even to try to understand what its own clients were doing. But it was never made public, even after the goings-on at Danske Estonia sparked one of the biggest money laundering scandals of all time.

In 2017, a team from OCCRP and the Danish newspaper Berlingske revealed that billions of dollars in dirty money had been moved through the bank’s Estonian branch. Only then, three years after it had been produced, did Danske’s head office get around to translating the Estonian audit.

Now, a copy of the report has been obtained by Berlingske and shared with OCCRP. It describes in exacting detail how the bank breached at least 47 different anti-money-laundering regulations — and how employees at the Tallinn branch enabled this by systematically ignoring hundreds of bizarre transactions.

In parts, it reads like a point-by-point list of the techniques offshore companies and politically exposed people use to transfer huge sums of money without accounting for their origin — and of the bank’s failure to question them.

“Danske was a textbook case where the bank’s risk level and its risk management were not in balance,” Kilvar Kessler, the head of the Finantsinspektsioon, or Estonian Financial Supervision Authority (FSA), told OCCRP.

“Why weren’t they? Because the profit coming from the branch with the risk was so high. If there would have been adequate risk control in place, such income wouldn’t have been possible.”

After seeing the first draft of his auditors’ report, Kessler was appalled. He immediately called Danske Estonia’s CEO, Aivar Rehe, and asked for a meeting. Soon afterwards, they were sitting together at an upscale restaurant in Tallinn’s picturesque Old Town.

“What have you guys been doing here?” he asked Rehe in dismay.

The bank head responded that without its lucrative offshore unit, Danske wouldn’t have a profitable business in Estonia.

Kessler asked if the head office in Copenhagen knew what was going on in Tallinn.

“Of course they knew,” he remembers Rehe saying.

Rehe committed suicide in 2019 amid a money-laundering probe into operations at the bank. He was not a suspect in the case but had been sought as a witness.

Danske Bank declined to answer specific questions related to this story. A press officer for the bank, Stefan Singh Kailay, directed journalists to a previous statement in which the bank acknowledged that it should never have had its portfolio of offshore customers.

“It is also obvious that we were too slow to acknowledge the scale of the problems and get the portfolio closed down,” Kailay said.

Thousand-Dollar Paint Cans and Nonexistent Addresses

The heart of Danske’s dirty business in Estonia lay in what was known as the “non-resident banking unit,” a team of about a dozen bankers who catered exclusively to foreign customers in places like Azerbaijan and Russia.

Last year, OCCRP reported on how these bankers — known as “relationship managers” — actively helped their clients evade anti-money-laundering regulations by running offshore companies for them.

But even when they weren’t conspiring with their clients, the relationship managers were ignoring obvious signs of money laundering, the FSA audit found.

For example, they accepted documentation from clients written in Azerbaijani, even though nobody on the team spoke the language. (The bank’s official policy was to only accept documents in English, Estonian, or Russian.) When asked about this, the bank replied that one relationship manager, Oksana Lindmets, had “some knowledge” of Azerbaijani and supplemented this with Google Translate.

They also accepted documents signed by Stan Gorin, a Latvian who had become notorious for selling his identity as a nominee company director, even though at that point there were hundreds of media reports detailing how his name had been used for illegal businesses, from weapons trafficking to pyramid schemes.

Perhaps most importantly, the relationship managers did not appear to pay much attention to the contracts that justified their clients’ transfers of millions of dollars, even when they were clearly absurd.

One high-risk client, Milecome Enterprises LLP, bought 10,500 one-gallon paint cans for an average price of over $1,000 each. Another supposedly sold a batch of metal pipes for $500 million, which would have added up to 344,820 metric tons — an unlikely amount, given that a full shipping container can hold only around 28. Inexplicable trades, especially those involving round numbers, are a classic sign of money laundering.

Another company, Riverlane LLP, was registered barely a month before it became Danske’s client. It had no website and only about 15,500 British pounds in cash assets, and declared its address at a location in Azerbaijan that didn’t appear on Google Maps.

Despite this, it almost immediately started moving huge amounts of money through the bank, mostly to other shell companies on the back of dubious contracts for the sale of electronics, textiles, building materials, and metals.

Auditors pointed out that many of these documents were nearly identical in form and content. In many cases, the buyer agreed to pay in advance for goods that would only be delivered after a month or more. One contract was signed a year before Riverlane was founded, while another was for the sale of an object whose name, the auditors said, was just gibberish: “the EP 70 KVA Sanay Puntasi 50cm.”

Danske often did not even bother to collect contracts at all, or check whether the trades actually took place.

“Danske Bank has not put in enough effort to determine where and when the goods would be delivered to the carrier and, moreover, whether the goods were carried at all,” the auditors wrote. “[F]or example, how and by what means were 282,138 tonnes of wire rod or workbenches valued at $250 million transported, and [were] they were transported at all.”

In just a year and a half, 65.7 million euros and over $1 billion passed through Riverlane’s accounts, an average of around $2.5 million for every working day — even though Danske never appeared to know who its customer was.

Drumming Up Business Abroad

In addition to its Tallinn-based “relationship managers,” Danske hired eight people in cities including Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kyiv, and Baku, whose job it was to drum up business for the offshore unit.

The bank claimed that these workers served a narrow function: promoting Danske to clients in far-flung locales, writing market analyses, and providing addresses to send and receive mail.

But in practice, the auditors found, they played a much bigger and more nebulous role, helping their new clients do everything from creating offshore companies to filling out bank documents.

Some of these contract workers worked on the same premises as . One of them, a woman in Moscow, even wrote on her LinkedIn profile that she was working for a formation agent called CPH Consulting ApS at the time she was hired by Danske.

Danske Bank only asked the contract workers to declare their financial interests once the on-site audit had already begun in 2014.

The ultimate line of defense against money laundering was supposed to be Danske Estonia’s Money Laundering Prevention Department, but auditors found they were not doing their jobs either. Instead of querying the relationship managers about large and unusual transactions, many interactions went like this, the audit report found:

- Payment arrives in the customer’s account in the amount of at least $/€ 500,000 …

- An employee of the Money Laundering Prevention Department sends a letter with the following content to the Relationship Manager: “Incoming payment to your customer. What is the economic activity and can the amount be credited to the account?” (Such correspondence is exchanged with Riverland LLP 25 times.)

- Relationship Manager’s reply is [a] copy-paste of the customer overview in the customer folder …. Every time, the Relationship Manager respon[d]s with the sentence: “‘Please transfer the money to the account.”

- An employee of the Money Laundering Prevention Department is satisfied with the answer every time and allows the amount to be credited to the account.

- Each next time, the Relationship Manager’s reply is repeated or again copy-paste is made of the customer overview in the customer folder.

The auditors said they had no confidence in the anti-money-laundering workers’ “education, necessary abilities, personal qualities and other professional qualifications” — or in Danske’s ability to monitor the funds flowing through its accounts.

“Consequently,” they wrote, “Danske Bank will not be able to prevent the use of the financial system and economic space of the Republic of Estonia for money laundering and terrorist financing.”

“How Is It Possible to Understand Such Transactions?”

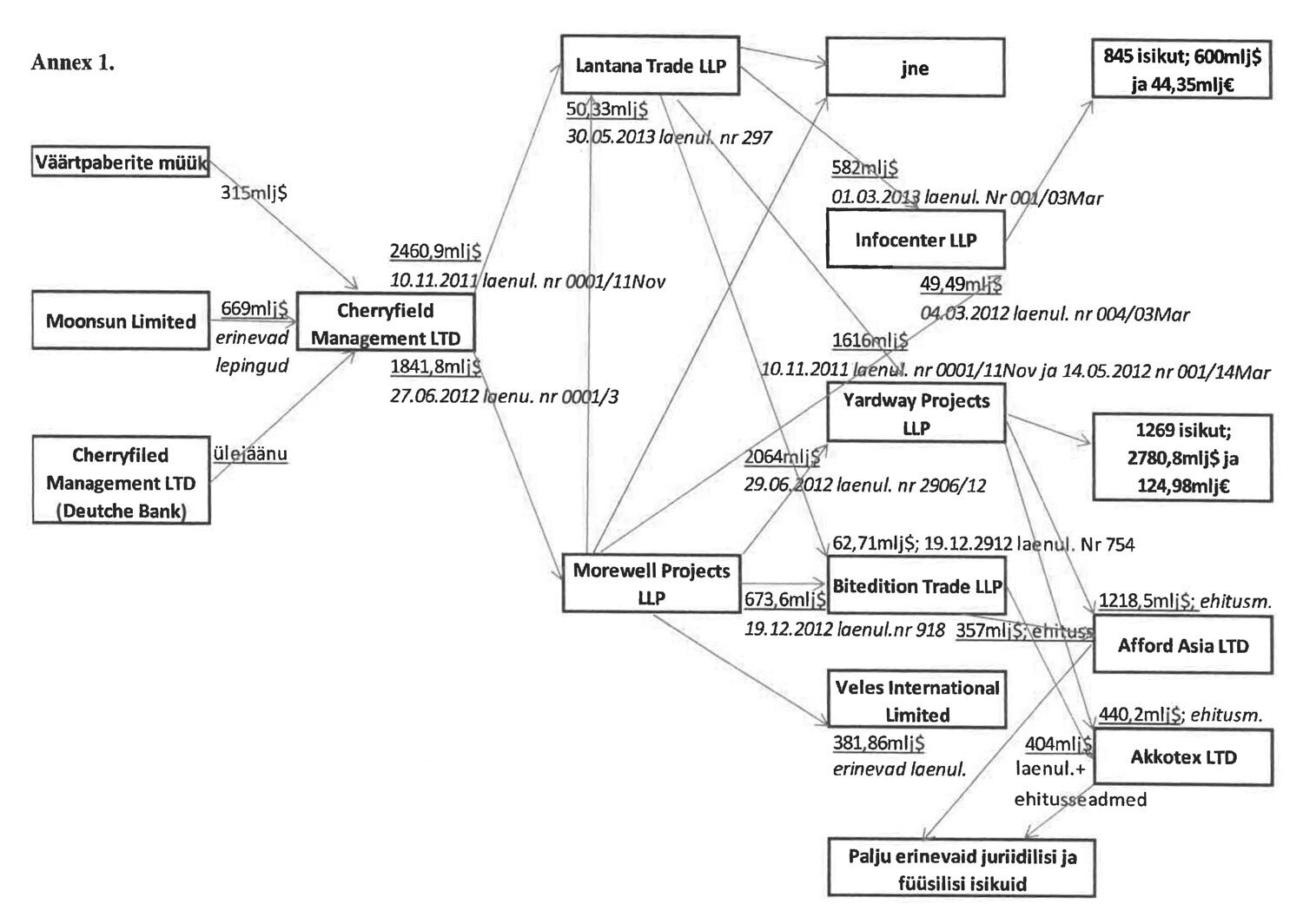

Perhaps the most egregious example of Danske’s failure to enforce anti-money-laundering regulations was the so-called “Lantana group” of customers: around 20 companies that were cycling huge amounts of money through Danske accounts in Estonia.

All were connected to a U.K.-registered firm called Lantana Trade LLP, which was later revealed to be closely connected to Igor Putin, the cousin of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Although most of the Lantana group companies had been created only a few months before they set up their business at Danske, the bankers quickly raised their transaction limits at the clients’ request.

Lantana Trade itself started with a limit of 2 million euros a day or 10 million euros a week in November 2011. Less than three months later, the limits had been raised to 7 million euros a day, and 30 million a week. By July the following year it had ballooned to 90 million per week.

During one period, Lantana’s “relationship manager,” Olga Tshetverikova, viewed the company’s accounts 17,558 times, or over 36 times every day, Danske Bank told the auditors.

Despite this, neither she nor anyone else at the bank made efforts to flag Lantana’s large and unusual transactions, like the receipt of over $1.8 billion from a company in the group on the back of an unspecified “loan agreement,” the bulk of which it quickly loaned out to yet another company in the group.

“It is not common that the high risk customer … established [a] few months before establishing the relationship [with the bank], about who there is no information at all according to the Google search engine, who does not have a homepage and whose place of activity is often in apartment buildings … is able to generate such turnovers,” the auditors wrote.

By mid-2013, the volume of money being moved by the Lantana group had become so inexplicably high that it was impossible to ignore, even for the non-resident banking unit.

Danske “had a very bad feeling” about the situation, the bank’s head of international and private banking, Juri Kidjajev, told auditors the following summer.

“How is it possible to understand those transactions?” the bankers were asking themselves, according to Kidjajev.

At that point, by law, Danske should have fired these clients, blocked their accounts, and reported their suspicions to Estonia’s Financial Intelligence Unit, which would have triggered an investigation.

Instead, the bank tipped off the Lantana companies and suggested that they essentially fire themselves. This allowed the clients to walk away with all their funds intact — and Danske to avoid an investigation.

“By acting in the described manner, [the bank] gave the Customers belonging to the ‘Customer Group’ the possibility … to leave without any possible consequences,” the auditors wrote.

Kidjajev explained Danske’s actions by saying that the bank “only had a feeling” that money laundering was taking place, but no proof.

Big Transactions and Powerful Relatives

In March 2011, the bank accepted as a client an Uzbek man named Akbar Abdullaev, along with a company he had opened two months earlier, Britman Sales LLP.

Abdullaev’s personal banker had never met him — a violation of “Know Your Customer” guidelines that banks use to prevent criminal money from entering their systems. She had also apparently never bothered to Google him, or she would have found that he was a cousin of then-Uzbekistan President Islam Karimov and was widely considered a possible successor to the authoritarian leader, a relationship that should have subjected him to extra scrutiny.

Publicly available information connected Abdullaev to possible money laundering , and he was arrested in his native country of Uzbekistan in October 2013. But despite this, he continued to be Danske’s client and even made two significant money transfers three months afterwards, including one in the amount of $10 million.

Danske Bank only started looking into his background in 2014, after the Estonian FSA started asking questions. A bank employee then identified him as a relative of Karimov and found “some negative information from [the] Internet about the customer,” the audit said. The bank asked him for additional data, but Abdullaev still hadn’t responded two months later.

(OCCRP sent questions to Abdullaev via a business partner but received no response.)

The auditors also found that Abdullaev had personally received dividend payments worth 20 million euros from his company, Britman Sales, though the bank hadn’t seen any justification for that figure.

Britman’s first listed address appeared on Google Maps as a point in the middle of an intersection. The company declared that it sold building materials and had around 5,600 British pounds in assets, and 1,500 pounds in liabilities.

Despite this, it moved over 63 million euros through its account at Danske Bank in under two years, often explaining the transactions as “loan agreements.” In one case, Britman sent 47.7 million euros to an obscure company with just one word of explanation: “own.”

Auditors were also not convinced that Britman’s contracts were genuine. Many were virtually identical, suggesting they had been copied and pasted in bulk.

On January 12, 2012, Britman signed an English-language contract to deliver 400,000 euros’ worth of building and finishing materials to a port in Finland, while the Russian-language version of the same document said the materials were worth 1 million dollars and would be delivered to Russia. Then, another nearly identical contract signed on the same day repeated these errors.

In another case, Britman earned $500,000 by selling 5,000 tons of cement, supposedly to a Slovakian company, and said it would deliver the load to an obscure railway station on the Russian-Latvian border. Danske did not ask even basic questions about this odd transaction.

“How and by what means were 5,000 tons of cement transported” to the railway station, the auditors wondered. And where did Britman get 5,000 tons of cement in the first place?

As for Abdullaev, the auditors pointed out that he was arrested in Uzbekistan in 2013, and there was no public indication he had ever been released. Despite that, he was signing contracts and making transactions through his Danske account in January 2014.

The auditors suggested that someone else had signed these documents in Abdullaev’s name.

“It is possible that this person was an employee of Danske Bank,” the audit said.