May 24, 2019//-It was close to midnight when the young man crawled into the desert.

All around him was darkness. A hundred metres away, a handful of Tuareg rebels and people smugglers, who worked together ferrying migrants through this unforgiving stretch of the Sahara, were gathered around three trucks, drumming and dancing and letting off long bursts of gunfire that rattled the night sky.

He could just make out the faint light from their phones, and every fifth bullet they fired was a tracer that lit a bright arc towards the stars.

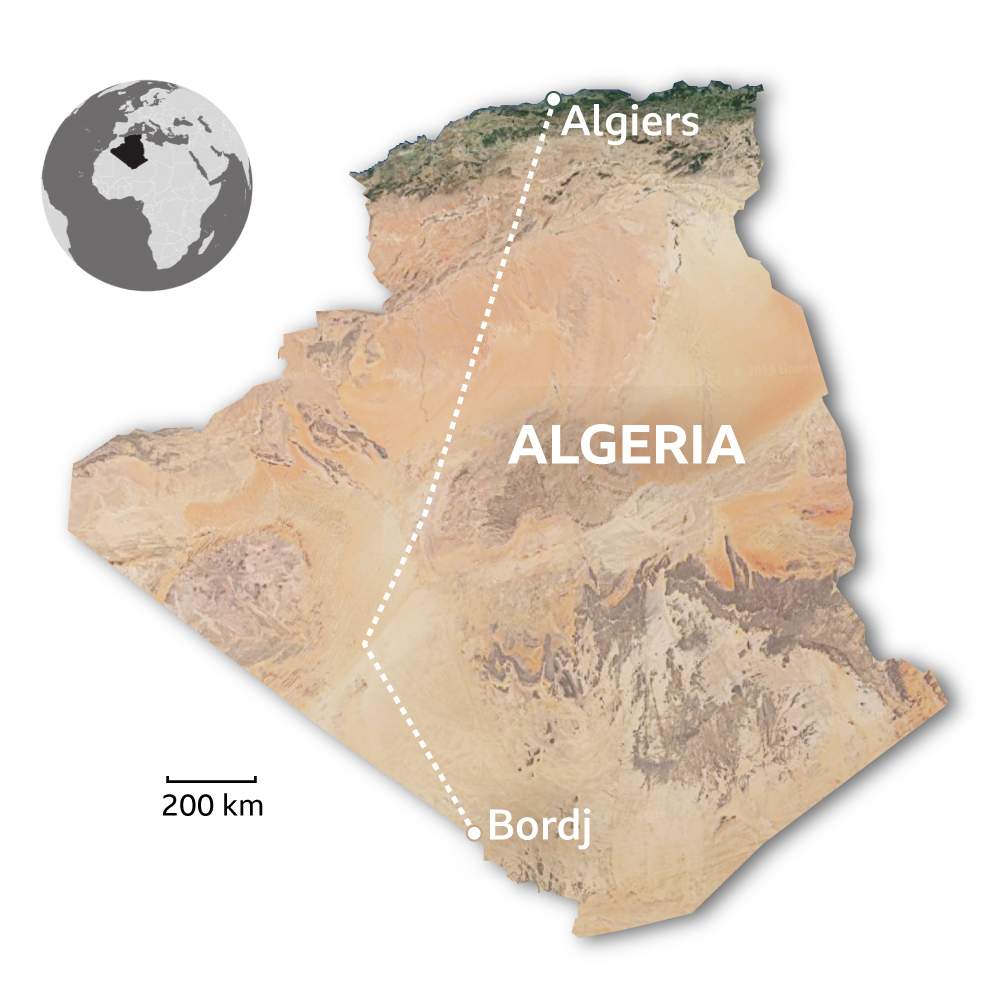

The young man, who had given himself the name Azeteng, was somewhere in northern Mali near to the border with Algeria. Behind him lay El-Khalil, a bleak and brutal waystation on the West African migrant route to Europe. Ahead of him, sand stretched for miles in every direction. He was a speck on the dark sea of the Sahara. Slowly, painfully, he pushed his body on, trying to keep as low as possible to the ground.

Azeteng was on the run. A few hours earlier, the smugglers who controlled El-Khalil had swiped his glasses from his face, just to mess with him, and refused to give them back. Azeteng was 25 but he was small for his age — 5’ 5” and slightly built, with a shy manner and a way of moving through the world that suggested he was always trying not to be seen. He was powerless to stand up for himself, so he backed away.

If the smugglers had stopped then to look closely at his glasses, they might have seen the strangely thick frame, the mini-USB port under one arm, the pin-sized hole in the hinge — and they would surely have killed him. He had seen enough already to be sure.

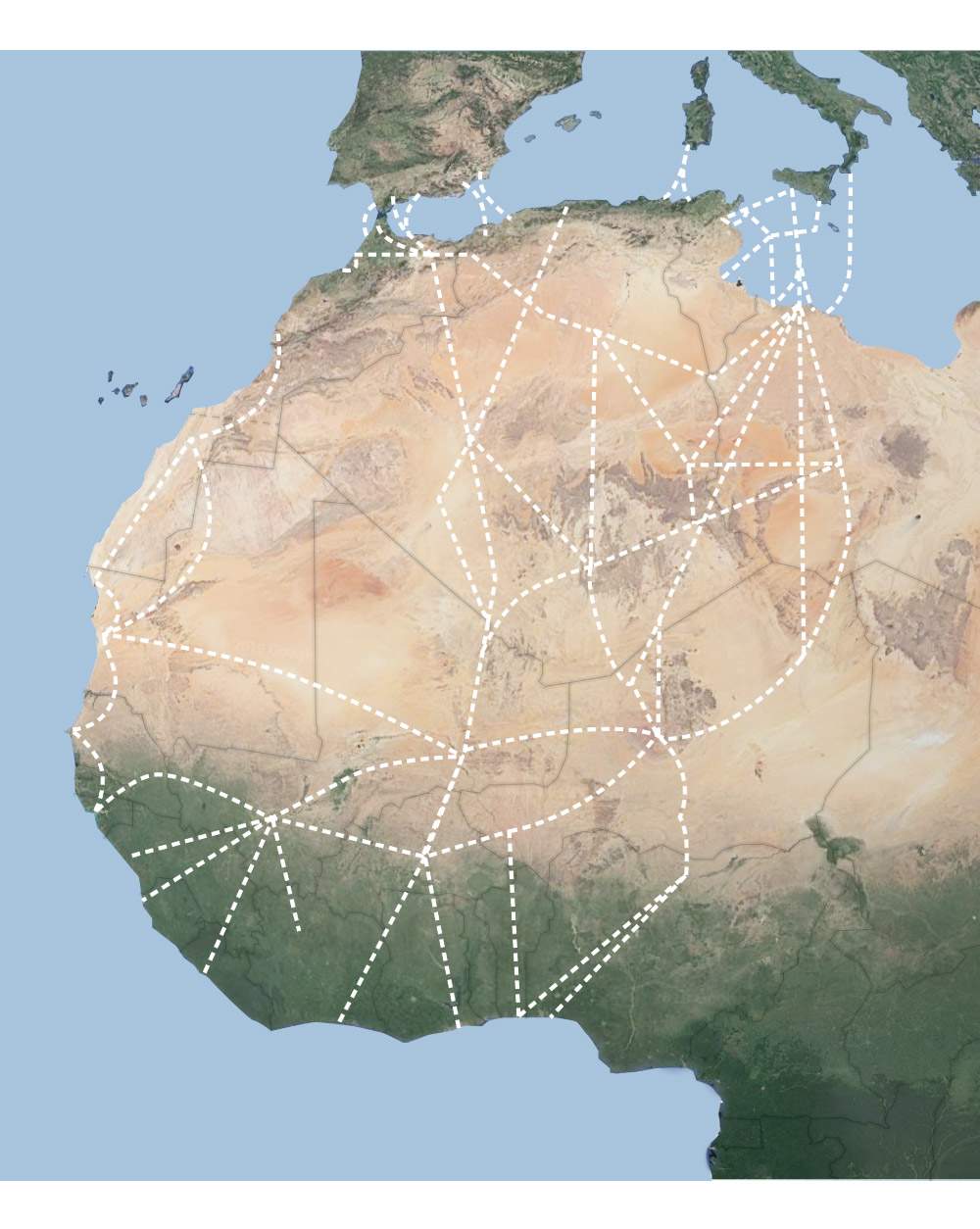

The month was May 2017. The migrant routes through northern Mali were controlled by the Tuareg rebels, who worked with smuggling and trafficking networks connected to departure points across West Africa. Azeteng’s journey began in Ghana. Others came from Guinea, the Gambia, Senegal, Sierra Leone.

In recent years, tens of thousands of men, women and children made their way into the Sahara, drawn by the distant promise of a better life in Europe.

A Ghanaian migrant who set out in 2016 told me he turned back in fear after hitting the desert. His friends persevered, towards Libya, he said. “Only one succeeded, to Italy. Later he told us that the rest were dead.”

Those who attempt the desert crossing travel along ancient trans-Saharan trade routes through Mali and Niger to Algeria and Libya and on to the sea. News reports have focused on the grim toll of the Mediterranean, which claimed the lives of more than 5,000 migrants the year before Azeteng set out. But according to UN estimates, as many as twice the number of migrants have died in the desert.

Those who attempt the desert crossing travel along ancient trans-Saharan trade routes through Mali and Niger to Algeria and Libya and on to the sea. News reports have focused on the grim toll of the Mediterranean, which claimed the lives of more than 5,000 migrants the year before Azeteng set out. But according to UN estimates, as many as twice the number of migrants have died in the desert.A few weeks after Azeteng crawled out of El-Khalil, 44 Ghanaians and Nigerians, including young children, died of thirst in Niger when the smugglers who brought them that far ran out of fuel.

Weeks later, at least 50 migrants died when three trucks were abandoned for unknown reasons. Those were the headlines. Many more would die uncounted in the sand.

Hail Mary full of Grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed are thou among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb Jesus. Holy Mary Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.

Outside El-Khalil, Azeteng prayed. For now, at least, the smugglers seemed too preoccupied with partying to notice the young migrant crawling in the sand, or pay much attention to the strange pair of glasses he had been wearing. When Azeteng thought he was far enough away to be safe, he stood up, brushed the sand from his clothes, and walked into the desert.

Azeteng was a middle child but an odd one out. Of his seven siblings, he was the only one with a different mother. He grew up on a rural police barracks in northern Ghana with his father, step-mother, and three half-sisters in two rooms. His own mother lived in central Ghana, and when Azeteng’s father was away, which was often, Azeteng felt like a stranger in his own home.

He was supposed to follow his father into the police, but Azeteng dreamed of being a spy. He spent his pocket money on James Bond films and low-budget CIA thrillers, burned on to blank DVDs by traders at the local market.

On the weekends, when his father sent him to cut grass for the family’s livestock in a garden behind the police station, Azeteng would pretend he was on a mission, and tiptoe up to the door to listen in.

What he heard on those weekends killed off what little ambition he had to join the police. He heard poor women come to the office to report that their husbands had beaten them, only to be told they would have to pay for a pen to take their statement, or for petrol to drive to make arrests.

The tricks were cheap, and the sums pitifully small, but they had an outsized impact on young Azeteng. When he saw prisoners whipped with sticks in their cells, he knew for sure he would not be a policeman after all.

As a teenager, Azeteng carried a pocket radio everywhere. His whirring, detail-driven mind catalogued the world around him, but sometimes struggled to discern which details were important and which were not.

He wanted to fight against injustice, but he didn’t know how. After high school he went to work with his mother in the fields of Kintampo, and at night he listened to his radio and imagined himself as an undercover journalist.

He had already reported one story, at his high school. Using a flip phone to secretly film, he exposed a group of teachers who were brewing alcohol on school grounds and ‘taking money from students for grades’, and when the story made the local papers, three teachers, including the headmaster, were sacked or transferred.

Lying in bed in Kintampo after working in the fields, he dreamed of telling a bigger story, exposing bigger crimes. On the radio, the news bulletins said young people from Africa were dying in their thousands in the desert and the sea.

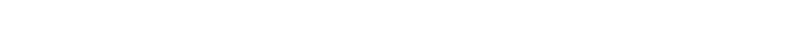

Six months later, Azeteng boarded a bus to Abeka Lapaz in the west of Accra, where he walked along the side of the nine-lane George W Bush Highway until he reached a nondescript two-storey building, home to CSIT Limited — purveyors of computer products and technical solutions, including secret cameras. He had already done some research into the various types of secret camera available. There was the button, the pen, the clock, the watch, and the glasses.

At 200 cedis — about £30 — the glasses were the cheapest. They were capable of recording only low-resolution images and they worked poorly at night. Later, British police would have to examine the footage carefully as they pieced together Azeteng’s story.

But as he looked at himself in the mirror in that day, Azeteng was just pleased to see it would take a second, third, probably fourth glance to spot that anything was amiss. He bought them, and called them his secret spectacles.

For five months, while he saved, Azeteng practised filming and hiding the memory cards in his mouth — a trick from a spy film. Then he sold his livestock — two sheep, six goats and 10 chickens — and set a date to leave.

At this point, no-one knew about Azeteng’s wildly dangerous idea except for Azeteng. So he told his priest: he intended to get himself smuggled on the desert migrant route to Europe, using a secret camera in his glasses to document the crimes of the smugglers.

The priest asked him if he had considered the dangers involved. Azeteng said he had. “I thought it was a service to the world, a service to restore human dignity,” the priest told me later. “I said I would offer Mass for him while he was away.”

Next Azeteng told his father, who lives now in a stone house on a small plot outside Accra. He still has the bearing of a policeman, though slightly faded by retirement, and he still rears livestock, which roamed the plot while we sat inside, away from the fierce afternoon sun.

“I was mad, mad because I couldn’t understand why he wants to take that risk,” he said. “Sincerely, I did not give him my blessing. Then he called to say that he had taken off, and I said, well, that is his choice. God be with you.”

Azeteng had packed a few items of clothing and made a razor cut in the lining of his rucksack to hide his cash. Then he walked to Kinbu Junction, a teeming transport hub in downtown Accra, and asked three young men if they were going north. They said yes, they were headed for Europe — across the water to Italy or Spain. They gave Azeteng the number for a smuggler named Sulemana.

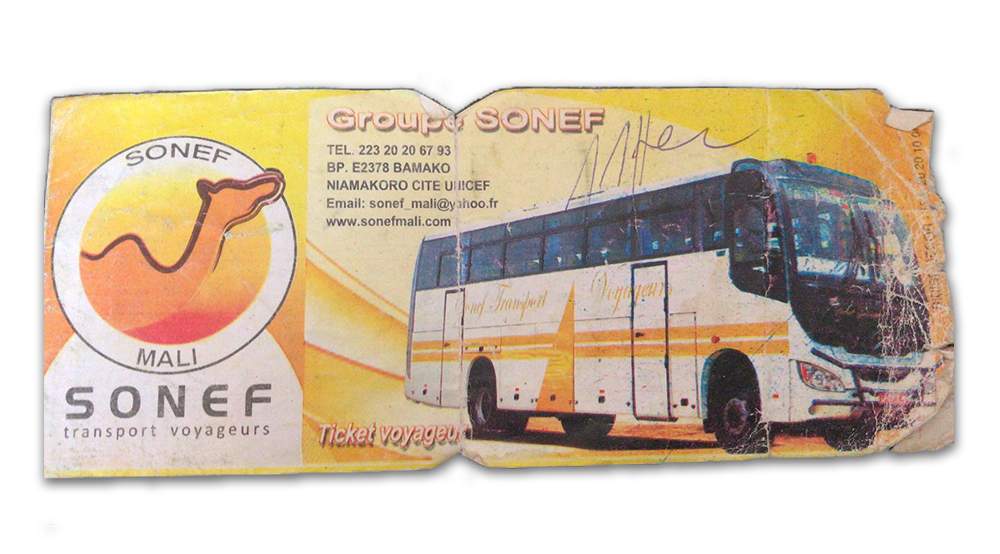

Sulemana told Azeteng to board an ordinary bus to Bamako, the capital of Mali, where they would meet. Azeteng had taught himself to record phone conversations, and he recorded his conversation with Sulemana and took detailed notes. The bus pulled out of Kinbu Junction. Azeteng wrote in his diary: “Saturday, April 15, 2017 — depart for Mali. 9.15am GMT.”

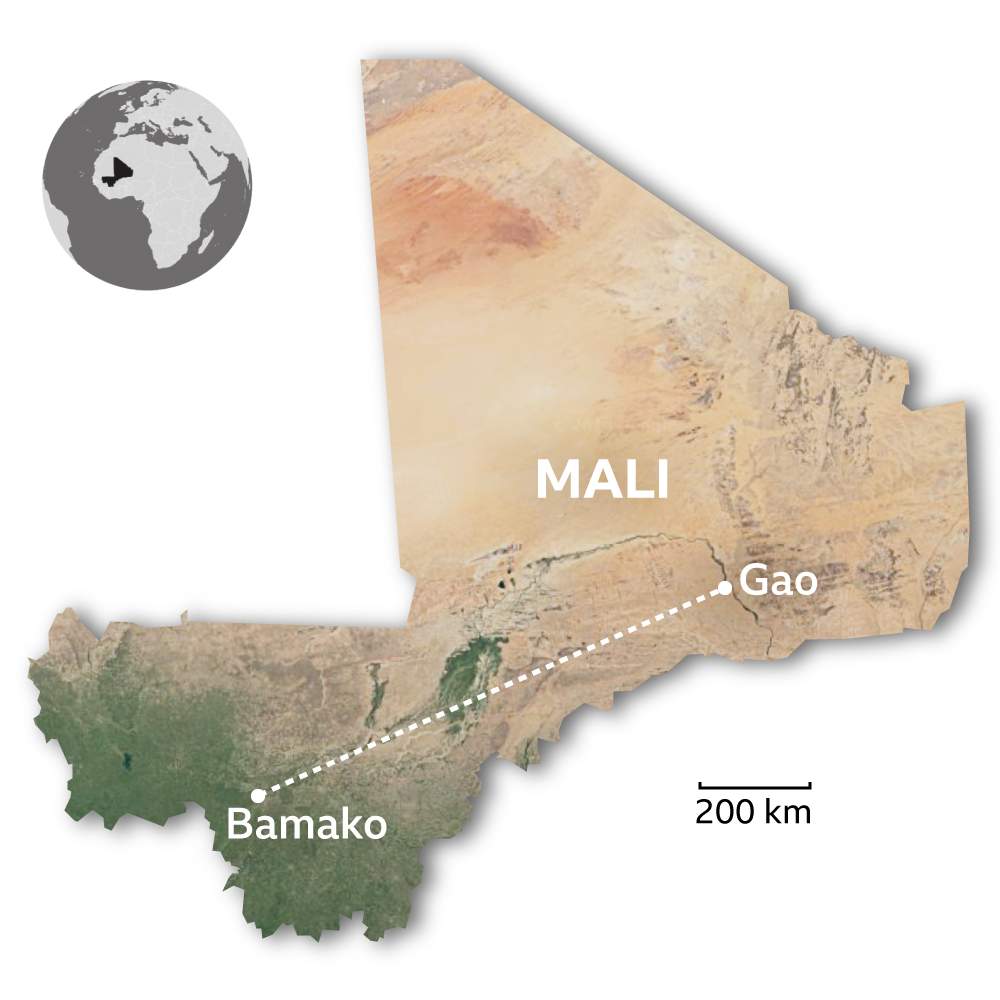

The bus crossed into Burkina Faso and then Mali, via checkpoints where small amounts of money were extorted by the police. After three days they reached Bamako. Sulemana arranged a fake travel vaccination certificate for Azeteng and demanded 45,000 CFA — £60 — for the next stage of his trip up to Gao, where Azeteng would meet Sulemana’s boss, Moussa Sangare.

At the bus station, somewhere close to a thousand migrants milled around in the heat. Azeteng took out his diary. “Every five minutes a bus will set off with African migrants and those trafficked,” he wrote.

“It is more like a busy international airport.” He wrote down a detailed description of Sulemana and the smuggler’s phone number, then he boarded the bus.

After a few hours, Sulemana called him. “If anyone asks you where you are going, tell them you are going to visit your relative,” he said. “Do not tell them you are going to Europe through the desert.”

Sulemana told him to prepare for his cash to run out, and to call home to ask for more along the way. “It is like I told you,” he said. “The road is all about money.”

After two days, the bus arrived in Gao — the gateway to the Sahara.

Gao is a city of hot dust-red streets and mud-brick houses, where migrants flow hourly into the city’s main bus station. Many, like Azeteng, already have a phone number of one of the city’s connection men, who house migrants for a few days before selling them on to be taken across the desert.

Anyone without a name and number is a target for coaxers — young men who board the buses outside the city to hustle migrants for their smuggling bosses.

Azeteng knew to ask for Moussa Sangare and soon he was in Sangare’s ghetto house. He moved through the house discreetly taking photographs with his flip phone and writing down what he saw.

Moussa Sangare appeared to take money from Malian security officers. He paid the connection men and boys who worked for him. When he had a certain number of migrants, he transferred them to the Tuaregs for the drive across the desert. Everything in his house — food, drinking water, a bath — cost money.

After three nights in Gao, Azeteng was called up to pay the $400 fee to continue north. Here was the final moment of safety before the dangers of the open desert. Ahead of the migrants lay at least six days in the Sahara, but in all likelihood many more.

EU-funded patrols were targeting the smugglers, pushing them to take longer, more remote routes. Trucks, laden with human cargo, became stuck. Migrants were dumped miles from cities and forced to walk, or waylaid for weeks as they worked to pay their way on.

Out on the desert, the lines between smugglers and traffickers, victims and perpetrators, would blur. Sand dunes would shift in the wind, leading even seasoned drivers astray.

But as Azeteng lined up to leave Gao, few seemed to dwell on the dangers ahead. The crowd buzzed at the imminent departure. In front of them were Toyota Hilux pick-up trucks which would ferry them to a warehouse to board larger, ageing transport trucks. Azeteng was packed into a truck with about 75 others — all men save for two Nigerian women, who sat up front with the driver.

Azeteng sat on the floor at the back of the second truck, his knees close to his chest, filming with his phone. Somebody switched on a small bluetooth speaker and the migrants sang and danced to pop music. Different languages and dialects rang out over the din — French, Bambara, Mandingo, Twi. As the convoy hit the open desert, excitement rippled through the truck.

The migrants were headed into northern Mali, a lawless black spot bereft of government forces, humanitarian agencies or journalists, controlled by militias and beset by jihadists. Azeteng sat quietly, a knot tightening in his stomach.

The rebels fired shots into the air and ordered the migrants to line up to pay. Those who didn’t have enough money were told to form a separate line and had their pockets searched and possessions taken. Then they were beaten. Azeteng was hit hard in the side of the head, knocking his glasses off his face.

A migrant in front of him was hit with a metal pole and bled from the mouth. A Gambian man, whom Azeteng had befriended on the journey, held up his Koran and begged in vain for them to stop.

Azeteng put his glasses back on and, overcoming a swell of fear, pressed the tiny button under the arm. The grainy footage captured the migrants shuffling past a militant holding out a large plastic bowl, depositing cash.

When the bowl was full, another militant tipped it into a larger bowl. Those who had paid were ordered to sit on the sand and wait. The wind whipped up and the cold started to bite.

It was then that Azeteng saw the two Nigerian women again, the women who had sat up front with the driver. Women from Nigeria, more than any other African nation, have fallen prey to the sex-trafficking trade to Europe.

A well-established criminal network entraps them with promises of well-paid jobs as hairdressers or houseworkers or similar, then sells them into sex work. “As soon as they leave their family and community network they become extremely vulnerable,” Michele Bombassei, a UN expert on West African migration, told me. “And this is the moment the sexual exploitation begins.”

Azeteng had spoken to the Nigerian women briefly, back in Bamako. They were confident and outgoing. They had joked and laughed. Now their heads were bowed, and Azeteng watched as they walked silently into the desert escorted by seven armed men from the checkpoint. The seven men gang-raped the two women on the desert floor, close enough for the migrants to see.

When it was finished, the women were brought back and put in the front of the truck and the migrants were put in the back of the truck, and a heavy silence settled on them. The jubilation of earlier that day had given way to fear.

No-one stood or danced or even spoke. Azeteng craned his neck and looked up at the stars, and they drove on through the night and the next morning and in the merciless heat of the afternoon they approached the second checkpoint.

It was the crack of a rifle bullet brought them to a stop a second time — a warning shot that fizzed over their heads. Azeteng picked himself up from the bed of the truck and looked out and a chill ran through him. For the first time in his life, he saw a severed human head.

Two severed human heads, mounted on wooden stakes — young men like him, he thought, probably migrants who made some small mistake. Horseflies buzzed around the heads, and blood had run down the wooden stakes and dried.

The migrants were ordered to get down from the trucks and line up, and the grim events of the first checkpoint began to repeat themselves — the cash bowl, the beatings, the Nigerian women.

Azeteng watched as the women walked again into the desert with half a dozen men. While the migrants waited, the driver of the truck, who looked to be in his late 30s and wore traditional Muslim dress, and had shared the front cabin with the women, removed a handful of sticks from a stash under the truck and slowly made a fire.

He filled a metal pot with water and poured in tea leaves and brought it to the boil. Darkness began to settle. The driver stirred the mixture for a while, and when he saw that the women were being brought back he poured the tea, and the three sat silently together by the small fire. The women’s faces looked so blank, Azeteng thought. Then the smugglers came shouting and rounded the migrants up.

They drove through the night, and the following morning brought more rebel checkpoints. At the fourth and final, Azeteng was hit in the leg with a metal pole so hard that he crumpled to the ground.

The migrants spent that night on the sand, and the Nigerian women were taken away to an area where the smugglers slept, shielded by a canopy from view.

When Azeteng awoke, a Senegalese migrant who was sleeping next to him — a tall, slim man in his 20s, who Azeteng liked because he laughed and played music and told loud stories about life in Senegal — said his arm itched. There was a small mark that had begun to swell. The migrants found a scorpion nearby and crushed it.

In the truck, the Senegalese migrant scratched the sting and began to complain of chest pains and a headache. Every few minutes he asked for water and the migrants gave freely from their bottles.

At the next stop, the border town of El-Khalil, the Senegalese migrant died later on the floor in a small room, surrounded by other migrants. The smugglers wrapped him in a white sheet and buried him in an unmarked grave in the sand.

Azeteng wrote in his diary. “In the desert there are no friends and no family, and only God stands as your friend. There is no water, no food and no trees. The desert looks like the sea, and the sun is unbearable.”

El-Khalil sits on the border of Mali and Algeria, a frontier trading post that began life in the early 1990s as an arms depot and evolved into an emporium for all manner of illegal trade — cigarettes, petrol, drugs, humans. Its mud-brick buildings are still bullet-scarred by a 2013 battle for control between Tuareg rebels and local Arab militia. Burned out trucks rest in the sand around its perimeter.

Azeteng and the rest of the migrants were told to hand over any ID documents then packed into small rooms and told to stay inside. They survived on biscuits and water, which was always hot from sitting in the sun in plastic drums. The fee to cross to Algeria was $100.

Azeteng offered to do chores for the smugglers in order to be near them. He ferried water and hung washing, and filmed them as they phoned migrants families to demand money transfers.

A humming generator powered chargers that kept the collection of phones alive, and the smugglers laughed and listened to music as they demanded $100 through Orange Money transfer or Western Union. Azeteng wrote down the names, dates and bank account numbers, and added them to his growing collection.

He was taking an incomprehensible risk. A week after he arrived, four migrants who couldn’t raise enough money escaped in the night, setting off to walk the 16km (10 miles) to the first town over the border.

The smugglers chased them down and brought them back — two alive, two dead. The migrants were rustled out of their rooms to watch a smuggler pull the bodies off the back of a pick-up truck.

“This is what happens to whoever tries to run,” the smuggler said.

From Azeteng’s footage: people smugglers in El-Khalil, who call migrants’ families and demand money transfers to secure the migrants’ safe passage

“The road is not good,” said Daniel, a Guinean migrant who had been travelling with Azeteng since Gao. “The rebels ask you for money and if you do not have it they will tie you like a dangerous dog and put you in the sun.

My god, my god, my god, this is very dangerous,” he said. “If you cannot pay the money you will never leave the desert.”

A woman who sold food to the smugglers from a small storefront told Azeteng a long and funny story about a love affair with a Liberian army officer who smuggled cocaine through El Khalil, and she railed about men in general. “Their brains only work at night,” she sighed.

Azeteng spent a little over two weeks in El-Khalil, until one afternoon he walked outside blinking into the sun, and was about to put on his glasses when he caught the eyes of a few idle smugglers, who beckoned him over.

Just as he had practiced, Azeteng took the tiny memory card out of his glasses and put it discreetly into his mouth. A smuggler snatched the glasses and tried them on and laughed.

Panic rose in Azeteng’s throat. Making too much of a scene would draw attention to the glasses, he thought, so he backed away, and in the dark of an outhouse, with the door wedged shut, he weighed his options. They killed migrants who tried to run. What would they do to a migrant spy?

They tie you like a dangerous dog and put you in the sun.

The words of the Guinean migrant rang in his head.

You will never leave the desert.

Azeteng waited in the outhouse until after nightfall, until he heard the sound of the smugglers drumming and the pah pah pah of their AK-47s firing into the sky. He knew he had to escape.

Before he left the outhouse, he moved his memory card from inside his cheek on to his tongue, and swallowed. Then he went to his room to grab his few remaining things — a diary, a pair of trousers and a T-shirt, assorted notes and bus tickets, and a one-litre bottle of warm brackish water — ran across a clearing, and crawled out on to the sand.

That night, his mind drifted in the dark. He heard voices at his back, but when he turned he saw only sand. What is this, he thought. Are these ghosts? Are these the voices of the migrants who have died on the desert? Is someone going to take my soul? Hail Mary full of Grace, the Lord is with thee.

His fear was compounded by a growing anxiety about losing his film footage — footage that was now in his stomach. He took the bottle of water from his knotted pullover and drank it in one go. Then he pushed his fingers down his throat until he vomited out the memory card, which he cleaned with his T-shirt and pushed into the pocket of his trousers.

The first stop inside Algeria was Bordj Badji Mokhtar, about 15km across the desert as the crow flies but 26km if you follow the road that cuts through the sand. Azeteng walked slowly in what he hoped was the direction of Bordj. He had no water and he stopped often to rest. Eventually, the sun rose, and in the distance Azeteng saw cars passing intermittently on the road.

When an Algerian army truck passed he thought he was saved, but it only slowed enough for the soldiers to throw a bottle of water at him and laugh as they sped off. A second truck carrying ice stopped and the driver gave him ice, but wouldn’t take him.

A third truck stopped and the driver gave him bread. For the first time on his journey, he became truly convinced he would lose his life. Finally, a fourth truck stopped, and a tradesman agreed to take him to Bordj. He didn’t speak English and Azeteng didn’t speak Arabic. Silently they rode north.

Azeteng had been sustained by a fantasy borrowed from a movie — an undercover migrant on a mission to document the crimes of the smugglers. But by the time he entered Bordj, he had no papers, no money and no spy glasses, and the story he’d told himself began to unravel.

He stayed with scores of others in an apartment where migrants slept in every available space, and the smell of camel meat drifted in from the restaurant next door. A few days after he arrived, Algerian children threw stones at him and called him a “black migrant”. He wept in the street.

He would need to work in Bordj in order to earn his way onwards, and he set about doing construction — mixing concrete, plastering, tiling.

Sitting on the street one day, Azeteng saw Sekou, a young Guinean migrant he recognised from El-Khalil. Sekou was limping and bleeding from the nose and mouth. He had been severely beaten by the smugglers in El-Khalil, he said, and dumped in the desert 8km from Bordj.

Azeteng helped Sekou to a hospital. Four days later, Sekou was dead. Some smugglers collected the body, and Azeteng followed them to a migrants’ graveyard near the edge of town. He watched as they took Sekou’s body from the bed of a pick-up.

The dead man had been wrapped in a white sheet, one arm bound straight along his side and the other folded across his chest. They lowered the body into a shallow grave and covered it with sand and gravel and bricks. Adjacent to the migrants’ graveyard was a graveyard for Algerian citizens, with orderly plots and headstones.

The migrants were buried haphazardly and close together, with nothing to mark their passing but the disturbance of the earth. Azeteng began to count, first one by one, then in rough batches, and by the time he gave up he’d counted 700 graves.

Azeteng went from the graveyard to where Sekou’s few belongings had been left and picked out the dead man’s ID. In the picture, Sekou had closely cropped hair and a sharp, handsome face.

The details on the ID card were plain. Sex: Male. Nationality: Guinea. Profession: Trader. Year of birth: 1996. Azeteng put the ID card in his pocket. He needed to keep moving.

It was early June, and the smugglers said there would be cars leaving in five days for Algiers — a three day, 1,500km journey across the desert.

Azeteng went to an internet cafe, copied his memory cards on to a computer and emailed himself the footage. Then he wiped the files from the hard drive, like he’d seen in films, and prepared to leave.

Three days later he was crammed with 14 other migrants — two for each seat — into a Toyota Land Cruiser. Azeteng could not move enough even to look left or right or raise a water bottle to his lips. They were heading into an arid stretch of the Sahara that in the height of summer is among the hottest places on earth.

After about 10km, the cars paused so the driver could scan for Algerian army trucks from a steep dune, and the migrants stretched their legs. The desert looked like a rolling sea, Azeteng thought.

His teeth were sore and turning brown and he had given up trying to rub the sand from his hair. His limbs ached, particularly his leg, where a deep purple bruise had flowered.

The driver returned and the migrants were crammed again into the landcruiser and they set off, and after 100km they were transferred to a minibus for the long, largely featureless desert ride to Algiers.

Around the time Azeteng was crossing Algeria, the country was breaking in a new policy of aggressive migrant deportations that would see thousands of people dumped in the desert over the following year.

Sub-Saharan Africans were rounded up en masse — from the street, from construction sites, from their homes — and deposited in an empty stretch of desert called Point Zero.

According to Human Rights Watch, men, women and young children were forced, some at gunpoint, to walk up to 30km through the blistering desert heat until they reached the nearest town.

Ahmed Ouyahia, then Algeria’s cabinet chief, said that African migrants were a “source of criminality and drugs”. In reality, they were mostly a source of low- or unpaid labour on construction sites from Bordj to Algiers. Dozens of migrants who flowed back from Algeria through Niger in early 2018 reported being sold by traffickers into slavery.

Ibrahim Musah, a Ghanaian migrant who followed the same route as Azeteng, five months earlier, told me he was bussed directly to a Turkish-run construction site in Algiers to register, then to a compound where West African migrants slept on cots in temporary cabins, which is where he met Azeteng one day in June, and became the first person Azeteng told on his journey about his secret filming.

“He was doing a good thing,” Ibrahim told me. “But if the smugglers see you filming they will kill you. They will kill you,” he said. The pair became friends.

Ibrahim started out from Ghana with almost no money, and he was subjected to levels of hardship and brutality that Azeteng had paid to avoid. Locked into debt bondage, he worked for five months in Mali and Algeria with little or no pay. “It is so hard, so hard,” he said. “Work, work, work, work, work.”

He pinched a fold of his skin. “My body was not good, it changed because of no food.” Ibrahim walked for five days in the desert after he and others were dumped by the smugglers, he said. He saw hands and feet sticking out of the sand, and helped bury a man who sat down on a dune one day, closed his eyes, and died.

dfvsad

Days passed on the construction site in Algiers. Azeteng and Ibrahim were barely paid or fed, and raids by Algerian security forces became more frequent. When Ibrahim heard the Algerians were dumping migrants in the desert, he made his way to a UN camp in Niger and was repatriated to Ghana.

Azeteng left the site and spent a few nights on the streets in Algiers, then he did something he hoped he would never do — he begged. He was largely ignored or swatted away, until he approached a 21-year-old Algerian law student called Houssem, who became the second person Azeteng told on his journey about his secret spectacles. “I always remember his face, he was in a bad situation,” Houssem told me. “He was tired and confused.”

The two sat and spoke for a while, about racism, migration, life in Africa. Houssem asked Azeteng how much he thought it would cost him to get back to Ghana.

He drove Azeteng via his house to the bus stop, and gave him 35,000 dinars — £220 — for the journey home, and told him to stay in touch, and he never asked for the money back. “I did what my heart told me to do,” Houssem said. “That’s all.”

Azeteng boarded the bus and began the long journey home, via Mali and Burkina Faso, by smuggling routes and ordinary bus journeys, and in the early hours of 2 July he passed the Ghanaian border, and made the sign of the cross.

Neil Abbott is the only officer of the British National Crime Agency based in Accra. His job is to help local law enforcement agencies police major crimes, like drug smuggling, modern slavery and human trafficking.

In August 2017, Abbott was at a conference in Accra at the UN migration agency, the IOM, when an employee told him about a package that had appeared in their mailroom — a crazy story about a migrant spy.

Back at the NCA offices, Abbott paid a visit to the mailroom and found a brown paper envelope, hand delivered. “It was undercover recordings, photographs, interviews with potential offenders and potential victims,” Abbott told me. “He’d collected all this information, bus tickets, travel itinerary… He had leaflets about agencies and transport depots, he’d marked phone numbers, names, bank account numbers…”

After he’d got back to Ghana, Azeteng had compiled copies of his evidence into packets and delivered them to various UN offices and the UK, US and Ghanaian embassies. Then he waited, and he had almost given up hope when he got two calls in a week, one from the British and one from the Americans.

At the end of his long journey, Azeteng found himself, to his surprise, in a secure compound inside the British High Commission, on a leafy street in an upmarket part of Accra, telling his story to the UK National Crime Agency.

I met Abbott there in February, and asked him what he made of Azeteng’s journey. “As a law enforcement officer, clearly there’s a story there for us, and potentially a witness to crimes that we can do something about,” he said.

Abbott and a colleague debriefed Azeteng over three weeks, carefully going over his story and physical evidence. Azeteng excitedly met every question with detail after detail. He drew maps and handed over names, locations, and number plates.

Abbott and a colleague debriefed Azeteng over three weeks, carefully going over his story and physical evidence. Azeteng excitedly met every question with detail after detail. He drew maps and handed over names, locations, and number plates.Then three months later, in February 2018, Azeteng got a call asking him to come back to the NCA offices. They told him that parts of his evidence had been sent to law enforcement in Mali and used in operations in Gao that resulted in the arrests of suspected people-smugglers.

“I can’t go into who those people are, the specifics of it, because there are ongoing investigations and we don’t want to prejudice any prosecutions that may happen in the future,” Abbott told me. “However, proactive action was taken within countries such as Mali that resulted in positive outcomes for that country.”

The technical language masked something that had meant the world to Azeteng — his journey had not been in vain. He had gone undercover, and contributed in some way to fighting crimes against migrants.

He was elated. But Abbott told him something else too: that his journey had been foolish and reckless, and that he could just as easily have lost his life.

“He’s one young man on this epic journey and he’s put his life on the line,” Abbott told me. “Make no bones about it, the journey these victims go on, and they are victims — they start off thinking they’re going to get a better life and halfway through they run out of money and end up being trafficked, and they are in the hands of these merciless people.

“These stories happen daily,” he said. “I’m sure it’s happening as we speak.”

I visited Azeteng in February, at his home in a small town just outside Accra, where he lives in a single room in a stone and clay-soil hut that encompasses two rooms, of which the other is a sheep coop.

The building sits on the edge of a communal space with a rough dirt floor, overhung by washing lines and populated by meandering livestock, in a slum-like settlement built along the side of a rail track that runs through the town on a low gravel berm.

In a box in the corner of the room, Azeteng keeps all the bits and pieces he collected on his journey — bus tickets, pictures, memory cards, a fake vaccination certificate and more. One item still bothers him, and he takes it out occasionally to look at.

When Azeteng got back to Ghana, he went to the Guinean embassy and told them he needed help to find the family of a Guinean man who had died on the desert. “I have his ID card,” he told the ambassador’s assistant. “Name: Sekou. Sex: Male. Nationality: Guinea. Profession: Trader. Year of birth: 1996.” Azeteng waited for three hours, until the assistant told him the embassy could not help and ushered him out.

I asked him why he took Sekou’s ID in the first place. “That is someone’s son, someone’s brother, who knows, maybe even someone’s father,” he said. “I asked myself, how will his family know that he is dead? So I am trying my best for the family to be aware.”

It may be that the full effects of the recent wave of African migration towards Europe are not felt for years to come. Azeteng told me his story with care and attention and in meticulous detail, until, several times, he broke down in tears. “What I have seen with my eyes is not easy,” he said.

Of the tens of thousands who have died on the journey, most stories will never fully be known, even to their families. For some who return, the ordeal will continue, in the form of stigma for a perceived failure to provide. It is a generational trauma.

As the sun fell, we walked from Azeteng’s settlement through sandy backroads to a church for evening mass, led by the same priest he had confided in before he left. After the Eucharist had been administered and the tithe collected, and the parishioners had finished singing, the small congregation filed out into the night. There was a perfectly clear sky, and Azeteng lingered under the stars to wait for the priest.

“When I was walking alone in the desert, you could see the moon just like this,” he said quietly. “I saw an aeroplane overhead and its lights were blinking, and I prayed that it would fall and pick me up and rescue me.” I asked him what he would say to someone considering the journey to Europe. “You will never find greener pastures on the desert,” he said.

The priest emerged from the church and Azeteng thanked him for the sermon. Then he set off walking back in the direction of his room. He was saving up again, he said, but this time for a diploma in journalism. In a felt pouch in his pocket were his new secret spectacles. In his bag was Sekou’s ID.