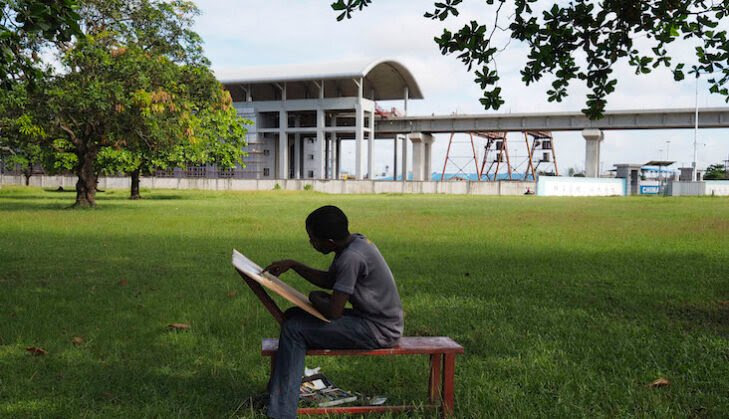

Much of Nigeria’s railway infrastructure was built by the UK colonial administration to facilitate governance and cheaply transport goods to the seaports for export.

Much of Nigeria’s railway infrastructure was built by the UK colonial administration to facilitate governance and cheaply transport goods to the seaports for export.

After falling into disuse for many years, the country’s railway architecture is now being modernised and rehabilitated.

The minister of transport, Rotimi Amaechi, is currently the man behind Nigeria’s recent rail modernisation drive.

One of the new rail projects, the Lagos-Ibadan double standard-gauge rail is facilitating real estate development along its corridors in Ogun and Oyo states, and could ultimately decongest Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital with a perennial congestion problem.

Many young Nigerians begin their corporate and business careers in Lagos, the commercial nerve centre of the country. Lagos is home to the highest number of SMEs in Nigeria and has just overtaken Nairobi as Africa’s top startup city according to the Global Startup Ecosystem Index 202, released by StartupBlink.

For all the opportunities, high housing rents in the state push them and other low-wage workers to live in the hinterlands. Those who opt to stay within the city to avoid productivity losses – which is one of the costs of commuting long distances in traffic to work — spend a big chunk of their salaries on rents.

These issues informed the decision by Andrew (not his real name), a senior associate at a Big Four company, to relocate to his hometown in Abeokuta late last year.

He tells The Africa Report that after Covid-19 forced his company to institutionalise remote work and the government’s promise to deliver the Lagos-Ibadan railway early this year, he chose to go back to his state to begin a new life.

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Two factors will determine the relocation or expansion of businesses to these areas, which will in turn create more housing needs. The first, the demand factor, is when businesses see new markets in these areas because more people are moving there”, says Abiola. “The second, the pull factor, is more significant. It has to do with deliberate government policy by the states to create industrial hubs along the rail corridor. In essence, the concerned state governments must be deliberate about creating business-friendly policies that will attract businesses to come over – security, intra-city infrastructure and such other incentives”.

The Oyo state government plans to acquire 15% equity in the Ibadan Dry Port to show its readiness to attract businesses. The Ogun state governor has also said the rail line, which has freight stations in the state, fits into their transportation master plan.

This year, people are renting two-bedroom apartments for N900K to N1m in Abeokuta and Ibadan ($2,200 to $2,500). That was unthinkable few years ago.

For Akolade Edunwale, principal consultant at Scudo Consult Limited, a real estate company with deep roots in the Southwestern parts of Nigeria, the Lagos-Ibadan rail line is a game changer for the real estate industry and the rail adjoining towns. He said that from their trend analysis, the commercial and industrial spillovers from Lagos to neighbouring towns in Ogun have fuelled real estate development in those axes and that the development is expected to get up to Ibadan once the rail line operations become efficient over time.

“It is cheaper to acquire property in Ogun. Big companies now acquire hectares of land there to build their factories and supply Lagos as the commercial hub of the country. There is a lot of real estate investments going on there that you can now get property worth N15m – N45m ($37K to $110K) in Magboro-Arepo industrial axis (Ogun). When the rail line begins fast cargo operations with fewer stops such that cargos can get to Ibadan in about an hour, you can only imagine the real estate development that will happen in those areas,” Akolade says.

The real estate boss believes that the impact of the rail line is already being felt on property prices and that it is becoming increasingly clear that high-end investment destinations will proliferate across the region soon.

“This year, people are renting two-bedroom apartments for N900K to N1m in Abeokuta and Ibadan ($2,200 to $2,500). That was unthinkable few years ago. It shows that the Lagos workers who have the purchasing power are moving in and creating the demand. There are also properties now worth 120 to 130m ($292,000 to $316,000) in Abeokuta. That is about how much you buy houses in Lekki (Lagos island). That shows the prospects of high-end real estate investment in Abeokuta and Ibadan once there is an influx of people with the purchasing power from Lagos and real estate investors are incentivised to invest more since they get good returns,” he adds.

Nigeria’s housing deficit has reached 17 million this year and the country must provide 100 to 700 thousand housing units annually for the next 20 years to bridge it. Lagos alone shares 15% of this gap.

Akolade believes that people would move with their families to these new areas if the state governments concerned can ensure a developmental balance by providing basic social amenities and infrastructure that are obtainable in Lagos so that households wont feel out of place when they move to these new locations.

More tracks ahead

Nigeria’s 3,505-km-long, two-line major railway infrastructure stretching from Lagos (Southwest) to Kano (Northwest) and from Port Harcourt (South-south) to Maiduguri (Northeast) was built by the colonial administration.

The Abuja-Kaduna segment at the penultimate extreme of the Lagos-Kano Western Line was rehabilitated and commissioned as a standard-gauge line in 2016. The Lagos-Ibadan segment at the other extreme became operational in June this year after it was upgraded into a double track standard-gauge line.

Although passed by the Federal Executive Council, most of the remaining and new lines including the Ibadan-Kano railway that connects the Lagos-Kano line, and the controversial Kano-Maradi railway linking Northern Nigeria with neighbouring Niger Republic are either yet to be built or operational.

The country’s railway infrastructure, although just developing after years of neglect, generates so little when compared to the rail transport income of South Africa, a continental peer. South Africa’s railroads are over 20,000 kilometres-long and in 2019, they transported about 175 million passengers compared to Nigeria which moved only about 3 million people, according to their national statistics agencies.

Despite the lockdown-induced movement restrictions in 2020, South Africa made about $2.5bn from rail freight transport while Nigeria only generated about $700K from rail cargo movement the same year.

Bottom line

The minister of transport, Rotimi Amaechi, is the man behind Nigeria’s recent rail modernisation drive.

It has been rumoured that he, in the upcoming 2023 elections, has plans to pick up the presidential slot that is expected to be reserved for the southern part of the country (where he is from), in line with Nigeria’s unofficial regional zoning arrangement.

If he is indeed interested in the country’s top job, he can as well run on his rail modernisation drive, which is facilitating industrial and real estate spread along the rail corridors. But to resonate with all Nigerians across the six geopolitical zones, he needs more railroads to build his track record on.

The Africa Report