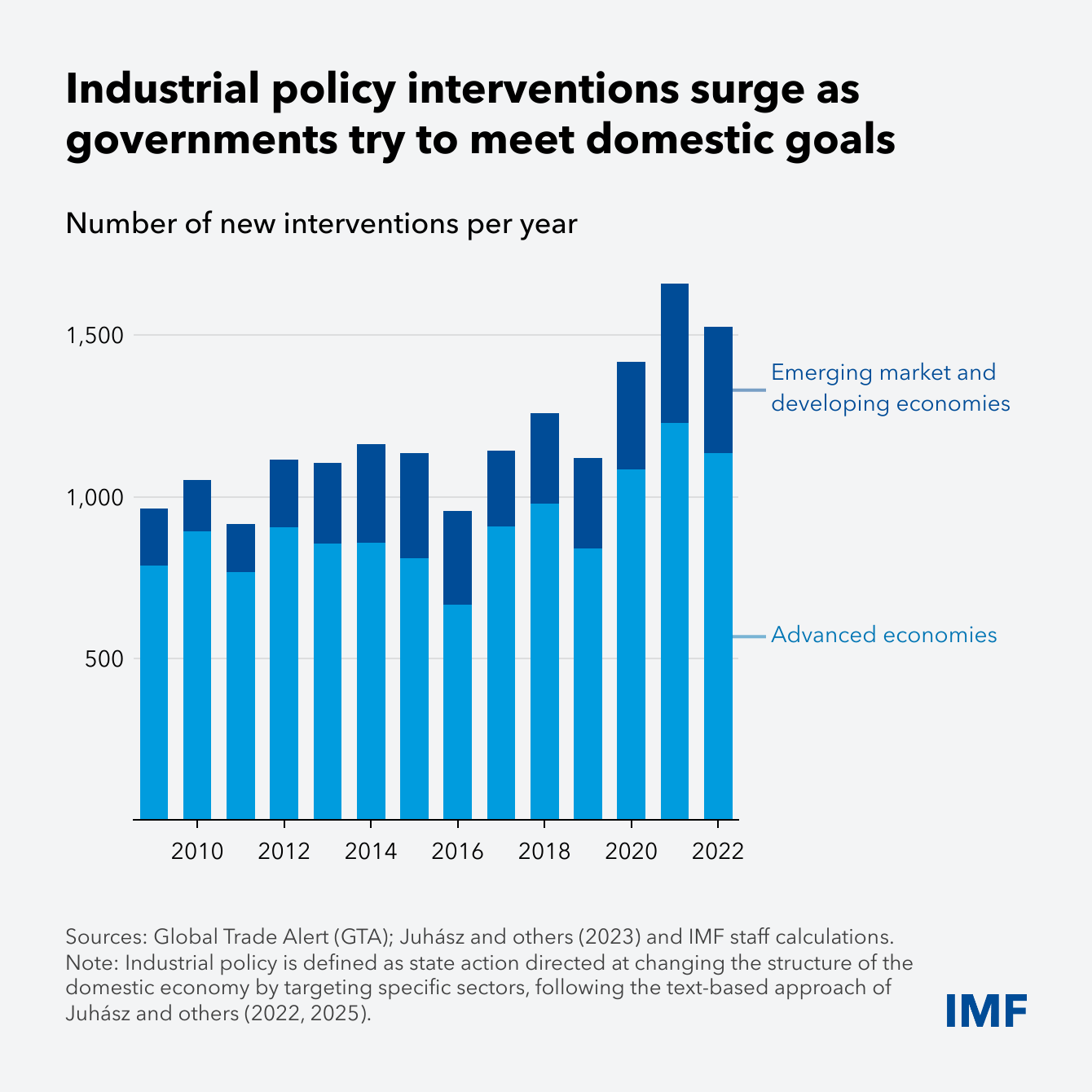

Governments across both advanced and emerging market economies have increasingly rolled out new support for targeted companies and industries over the past decade and a half.

Industrial policy, as it’s known, is used for a range of goals, including to boost productivity growth, protect manufacturing jobs, improve self-dependence and the resilience of supply chains, and develop “infant” industries to diversify the economy. In the energy sector, for example, some countries have used industrial policy to reduce dependence on imported oil and gas.

Such policies can help jump-start domestic industries and transform the structure of an economy. But gains are not guaranteed and can come with costs—both to government budgets and economic efficiency, as we show in an analytical chapter of the latest World Economic Outlook. Industrial policies involve trade-offs that countries should consider, according to our research using economic models, case studies, and empirical analyses.

So, how can countries design industrial policies to maximize their effects and limit the associated trade-offs?

Impact on targeted sectors

For a start, the effectiveness of industrial policies depends on industry-specific characteristics that can be hard to determine in advance. Our simulations show that industrial policy can help boost domestic sectors when productivity scales up with output. This could reflect workers learning on the job or industries becoming more efficient with scale.

Countries can use a mix of subsidies and trade protections to promote domestic production in strategic industries. In principle, early support through industrial policy can deliver dynamic gains and long-lasting productivity improvements in sectors that become more efficient with experience. Because production costs decrease as volume grows, targeted industries can learn by doing and become competitive globally.

However, these industrial policies come with significant trade-offs: consumers can face higher prices for a prolonged period, and governments can incur substantial budgetary costs. Success also isn’t guaranteed, because it depends on industry-specific traits that are often difficult to predict. Catching up technologically may not be achievable if companies are too far behind, learn slowly, or domestic firms can’t readily access large markets, for example, through exports.

Empirically, our analysis of the effects of recent industrial policies suggests industrial policy is associated with better economic outcomes in targeted industries, particularly in countries with strong institutions. But the gains are small.

Direct subsidies to an industry are associated with about a 0.5 per cent improvement in value added and 0.3 per cent higher total factor productivity three years after implementation, reflecting higher capital accumulation and employment.

These improvements are modest compared with the sample average industry value-added growth of 6.5 per cent per year and total factor productivity growth of about 4 per cent per year.

Moreover, earlier IMF analysis reaffirms that larger gains can come from structural reforms to improve the overall business environment and better enable credit access for all firms.

Aggregate impacts

While industrial policy can help specific industries, translating these into broader economic benefits can be challenging.

Our multi-sector, multi-country quantitative model shows that employment, productivity and output all improve in targeted industries. But, because resources are drawn away from untargeted sectors, those sectors end up shrinking and losing productivity, potentially delivering a negative impact on aggregate productivity.

So, even if targeted support can boost priority sectors and increase resilience and independence, our analysis suggests it can also create misallocation of resources and dampen aggregate outcomes, leaving the economy worse off.

Calibrating policy

Our findings highlight the importance of carefully designing and implementing industrial policy. Governments should consider the risks of wasteful spending, especially when debt is elevated and fiscal space is limited.

They should weigh the opportunity cost of industrial policy against economy-wide reforms that can often boost economic outcomes without relying on precise sector targeting or high fiscal costs. And they should recognise and manage trade-offs explicitly. Although not the focus of this chapter, large-scale industrial policy can also have cross-country spillovers and trigger retaliation by trading partners.

Countries that do pursue industrial policies should include mechanisms for regular evaluation and recalibration, all underpinned by a strong institutional and macroeconomic framework. Policymakers should encourage market discipline through vigorous domestic and international competition.

Doing so will increase the likelihood that industrial policy delivers on its promise—without compromising fiscal sustainability or economic efficiency.

—This blog is based on Chapter 3 of the October 2025 World Economic Outlook, “Industrial Policy: Managing Trade-Offs to Promote Growth and Resilience.” The authors of this chapter are Shekhar Aiyar, Hippolyte Balima, Mehdi Benatiya Andaloussi, Thomas Kroen, Rafael Machado Parente, Chiara Maggi, Yu Shi, and Sebastian Wende, with research assistance from Shrihari Ramachandra and Yarou Xu.