Over the past six months, the realignment of global priorities and increasingly turbulent external conditions have continued to test sub-Saharan Africa. Yet the region’s economies are proving resilient.

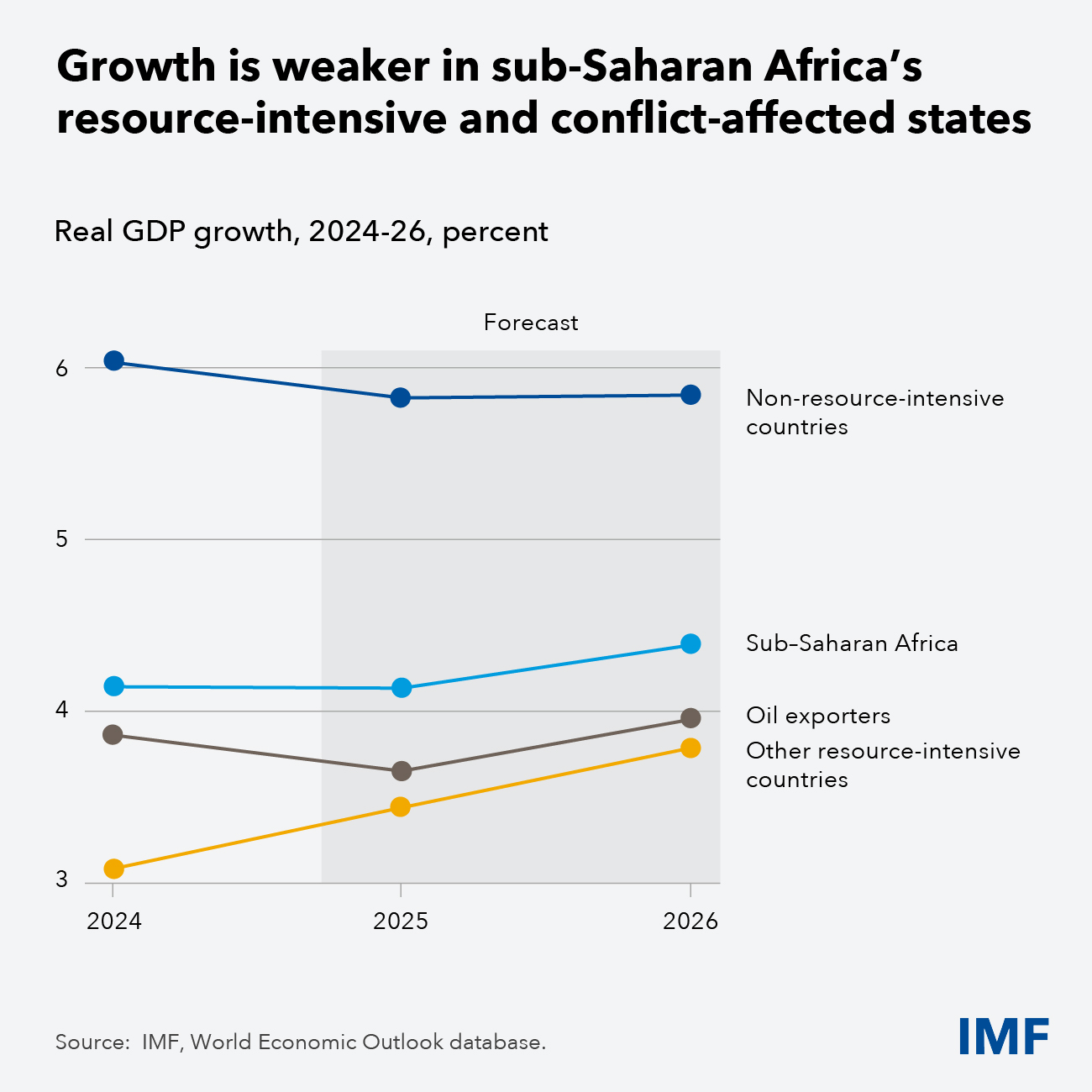

As our recent economic outlook for the region shows, economic growth is projected to hold steady at 4.1 per cent this year, with a modest pickup to 4.4 next year. Such steadiness reflects years of important reform efforts across key economies.

The region is home to several of the world’s fastest growing economies—Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Uganda. Yet, resource-dependent and conflict-affected states are struggling to sustain momentum. For them, gains in income per person remain modest—around 1 percent a year on average, and less in the poorest countries.

This divergence is partly a result of commodity markets pulling in different directions: oil prices slid since April, while cocoa, coffee, copper, and gold prices are up. Countries are also facing high borrowing costs, though lower than earlier this year. Angola, Kenya, Nigeria and the Republic of Congo recently returned to the international bond market.

The global trade policy and aid landscape has also deteriorated. Tariffs on exports to the United States have increased, and preferential access to the market under the African Growth and Opportunity Act has expired. While the amount of tariff-exposed trade is relatively modest for most countries in the region, the effects of trade tensions are likely to be felt through dimmer global growth prospects and volatile commodity prices.

Meanwhile, the sharp drop in foreign aid is hitting poorer and fragile states hardest. Governments trying to reprioritize spending also confront capacity constraints and limited room for maneuver in budgets.

Resilience tested

While sub-Saharan Africa’s resilience is encouraging, vulnerabilities have been building up and will continue to test the region. Many governments now face a challenging mix of fiscal, monetary, and external pressures that threaten hard-won reforms and could complicate responses to future shocks.

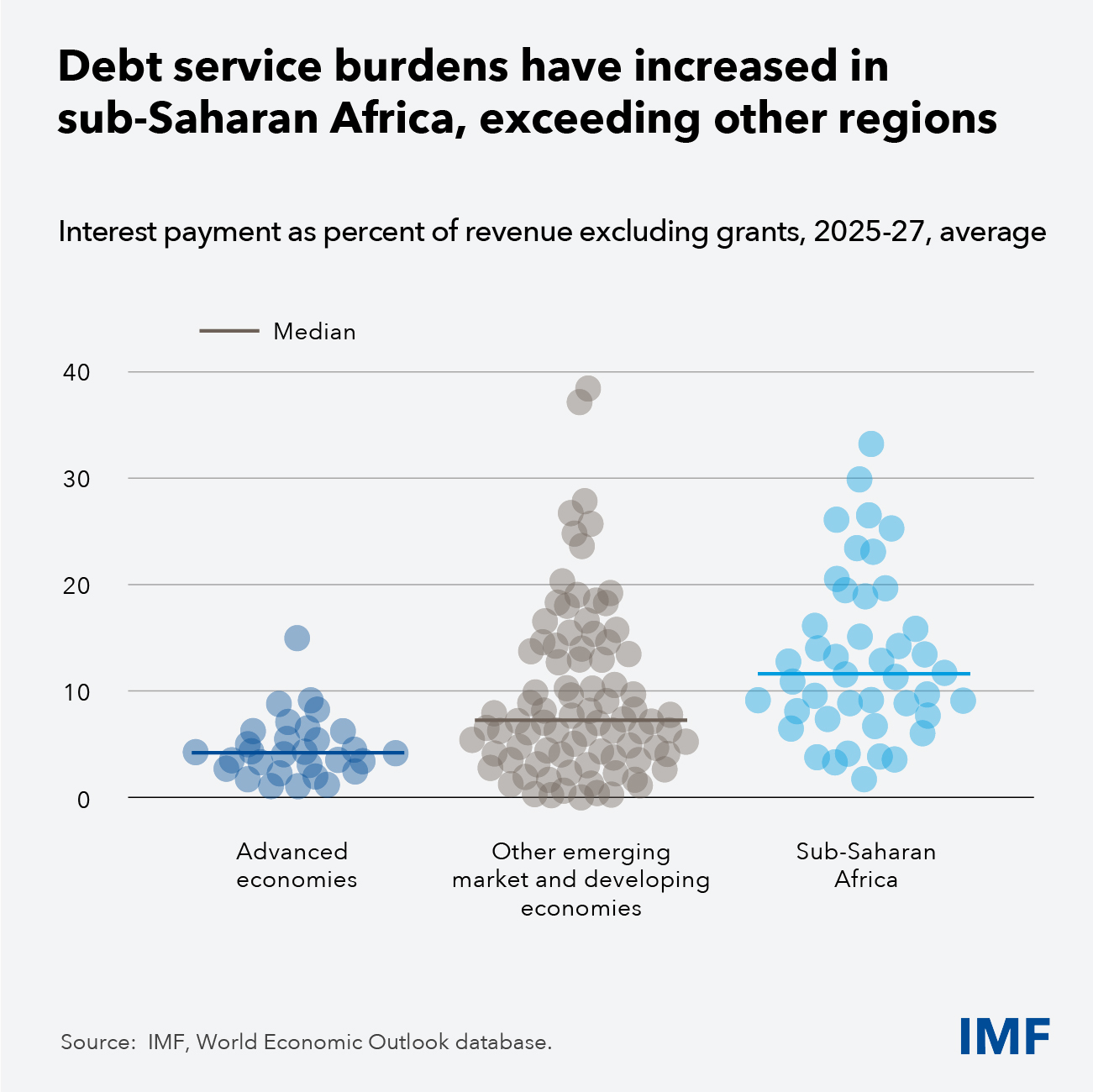

Debt service costs are rising fast, squeezing budgets and the space for development spending. Fiscal fragility continues to trouble the region, particularly among low-income economies. Twenty countries are now either in or at high risk of debt distress. And, as governments shift toward domestic borrowing, banks are more exposed to government debt risk.

Inflation, though easing overall, still exceeds 10 per cent for about a fifth of the region’s economies. And while some countries have rebuilt international reserves, they remain stretched across much of the region.

Against this difficult backdrop, we see two broad policy priorities.

Raising revenue

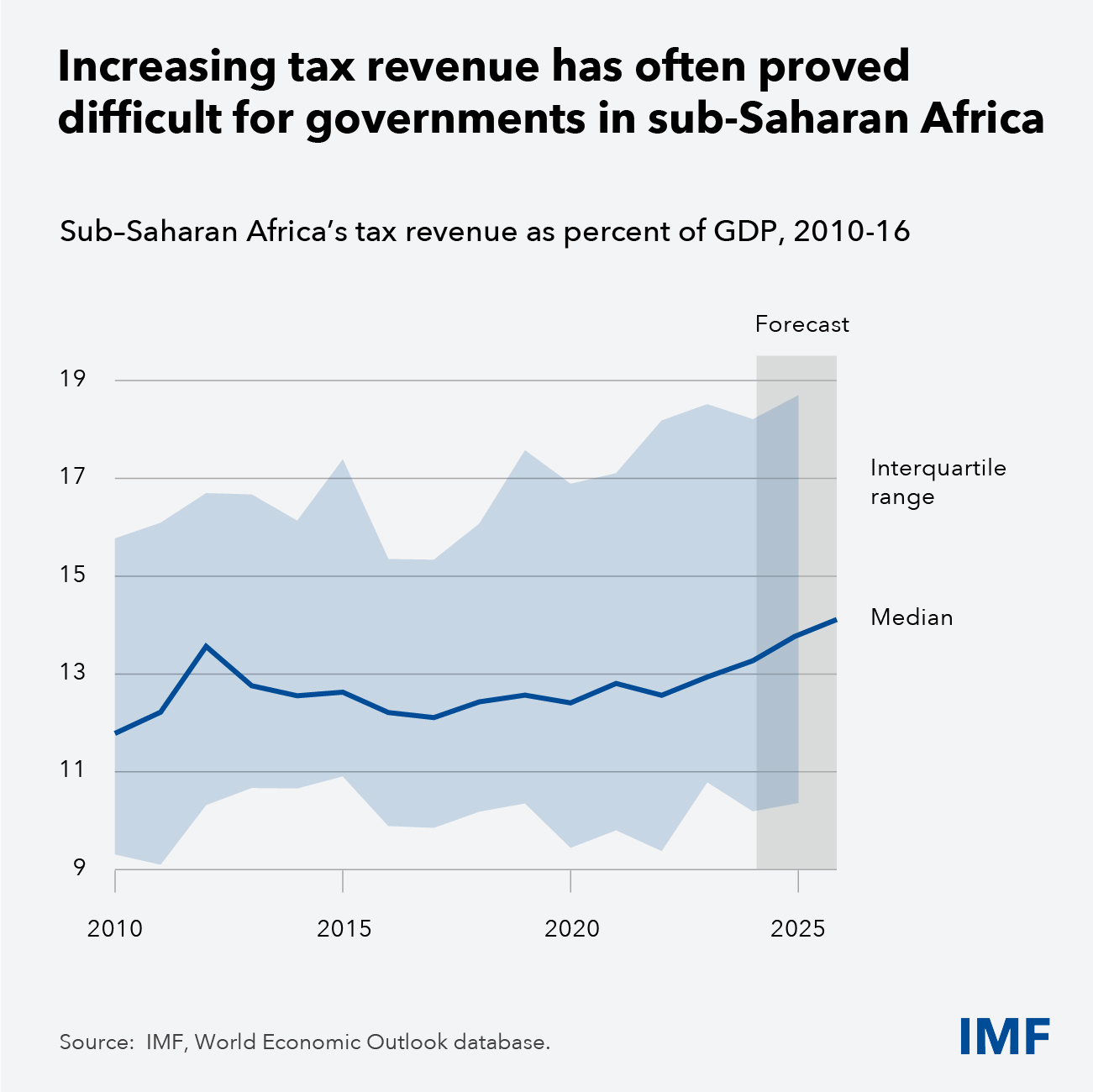

First, raising more revenue. The region’s development needs remain immense, yet external financing is scarce and debt burdens are heavy. Mobilising domestic revenues at home is an essential route to lasting fiscal space, while better debt management can lower borrowing costs and widen access to funds.

Boosting tax collection has long been a challenge for the region’s public finances. Past efforts show what works—and what does not. Effective reform demands attention to both tax policy (what and how much to tax) and tax administration (how to collect). Countries that have made headway—such as Ghana,

Rwanda and Tanzania—did so by digitizing their tax systems, piloting reforms, supporting tax officials, and engaging citizens. Others learned that limited public support can derail poorly designed levees. The lesson is clear: progress depends as much on trust and sequencing as on technical fixes.

Given that people are more willing to pay taxes when they see public money spent wisely, governments need to pair revenue reform with visibly improved service delivery, tighter spending controls, and efforts to tackle corruption and boost accountability. Without such enhancements, revenue gains will prove fleeting.

Managing debt

Improving debt management is also essential. Transparent, credible debt management institutions can cut borrowing costs and attract investors. Publishing comprehensive debt data, engaging openly with creditors, and strengthening approval and oversight procedures are key first steps.

Better debt management also supports access to innovative financing. Instruments such as blended finance, which combine concessional and private funds, can channel investment into green energy, health, and infrastructure. Agreements between governments and creditors to replace existing sovereign debt with liabilities that include spending for a specific development goal, known as debt-for-development swaps, can foster social or environmental gains—and have been tested in Côte d’Ivoire, among other places.

But to scale up such initiatives, governments need credible regulation, transparent data, and simplified procedures. These tools, used correctly, can help lay a foundation for more resilient and inclusive growth.

Abebe Aemro Selassie, Amadou Sy

—This blog is based on the October 2025 Regional Economic Outlook for sub-Saharan Africa, “Holding Steady,” prepared by Cleary Haines, Athene Laws, Maurizio Leonardi, Nikola Spatafora, and Felix Vardy under the guidance of Montfort Mlachila, Amadou Sy and Antonio David.