November 19, 2020//-Ghana has invented a special kind of political polarisation – as much personal as ideological – seen in the response to the demise of former leader Jerry John Rawlings on 12 November, 2020.

Second only to founding President Kwame Nkrumah, Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings shaped the country’s trajectory. And as with Nkrumah, his legacy is highly contested.

A wing of the country’s establishment went into mourning and prepared for state obsequies. Another wing rehearsed the bloody regime change of four decades ago, of generals marched to a firing squad and of three judges kidnapped and murdered at the dead of night.

At times, the divide between leftists and conservatives can be as sharp as in Europe and the United States; at others, there is incessant two-way traffic between the two camps, with each side stealing the other’s ideas.

Many of Ghana’s conservatives will never forgive Rawlings and his cohort for their attempt to set up a people’s republic in the early 1980s, blaming his strident leadership for the lives lost and economic descent of that era. At first, workers and students celebrated the reforming zeal of Rawlings, the ace air force pilot with an obsession for technical details.

‘His distaste for both political camps’

Later on, many radical activists and trades unionists, gaoled and detained for anti-government activities, became diehard opponents of Rawlings as he started his rightward march.

READ MORE Ghana’s tears, 30 years on

An exponent of no-party politics, Rawlings had tried to bypass the mainstream political divide. He rejected the socialist ideology of founding President Kwame Nkrumah but was deeply suspicious of what he saw as the elitist political tradition of Danquah-Busia parties.

“Rawlings’s style was a populism that connected with the urban youth across Ghana…”

Partly, it was his distaste for both political camps and his attempt to break the mould of mainstream politics that explains his dominant role in Ghana’s political life in the 1980s and 1990s. His scepticism towards establishment politicians and the generals resonated across the society.

At heart, Rawlings’s style was a populism that connected with the urban youth across Ghana, the same constituency that had been fired up by the anti-colonial struggle and recruited into Nkrumah’s verandah boys movement.

They were the dispossessed; central to political mobilisation and immortalised in Ayi Kwei Armah’s brilliant “The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born”.

‘Radical new alliance’

As Ghana shuddered after Rawlings’ first coup d’état in June 1979, socialists, radical nationalists and most of all, adherents of Nkrumah, joined this radical new alliance.

Once in power, Rawlings took up the siren call for ‘house cleaning’ and the ‘war on corruption’.

Activists at the heart of events recall there was more madness than method. First, a failed revolt on 15 May 1979 against the regime of Lieutenant General Fred Akuffo landed Flight Lieutenant Rawlings in jail facing a death sentence. Sprung from prison on 4 June by fellow junior officers, Rawlings joined the coup plotters in days of fierce fighting against stalwarts of the Akuffo regime.

Once in power, Rawlings took up the siren call for ‘house cleaning’ and the ‘war on corruption’. The immediate targets were Lt. Gen Akuffo, his predecessor Gen Ignatius Acheampong and five other senior officers – all of whom met their end at the army’s firing range at Teshie on the Atlantic Ocean.

To some surprise, Rawlings and the Armed Forces Ruling Council then presided over elections and handed over in September 1979 to Hilla Limann who won the Presidency on the ticket of the Nkrumahist People’s National Party.

It proved to be a short interregnum of civilian government. Endemic corruption persisted, with added political dysfunction. Rawlings and his allies plotted their return, seizing power on new years’ eve on 1981.

This time, they promised, there would be no premature exit.

It was the second coming of JJ or Junior Jesus, as his more fervent supporters had it.

‘The second coming of Junior Jesus’

In Accra, Tema, Takoradi and Kumasi, activists set up people’s and workers defence committees, designed to build community solidarity and negotiate better working conditions.

Some spun out of control when petty authoritarians tried to inflict their will on others, as in the public flogging of market women for kalabule, profiteering and hoarding their goods.

For those who looked to Cuba, an early supporter of Ghana’s revolution, the network of people’s committees were foundation stones for a new political structure, promising grassroots accountability, equality and international solidarity. A staunch journalistic hangover from the colonial era was renamed The People’s Daily Graphic.

Like many leftist regimes, the Rawlings-led Provisional National Defence Council had inherited a near bankrupt state. Many advocated radical redistributionist policies. Lands and factories were seized.

Bespectacled intellectuals took to carrying around Kalashnikovs and quoting Fanon on ‘revolutionary violence’. Portly political barons and captains of industry took flight.

Unnerved by the leftwards tilt of the new order, US and European governments were eager to see its downfall, egging on would-be usurpers. A succession of failed putsches added to the ferment of the time.

They were fended off by Ghana’s ruthless and highly effective security organisation, one of whose high points was turning a CIA operative in Accra who helpfully supplied the names of many Ghanaians collaborating with US intelligence. For unknown reasons, this script was never made into the Hollywood blockbuster it would have been.

But many in the once comfortable middle classes were torn between ridiculing what they saw as the jejune politics of the new revolutionary times and lambasting the fellow travellers of the new order who were driving their beloved Ghana into the welcoming arms of Moscow and Beijing.

Welcoming or not, neither Moscow nor Beijing in 1983 had the financial wherewithal nor inclination to bail out Ghana, brought low by a decade of corrupt and spendthrift military regimes.

Consolidating power as a military leader, Rawlings then presided over the imposition of a structural adjustment programme, negotiated with the IMF at its neo-liberal zenith.

The significance of that Faustian pact – the IMF gives Ghana an international financial imprimatur, reschedules the debt and reopens the credit lines in return for the surrender of economic sovereignty – appears even greater in retrospect than it did at the time.

‘Rawlings’ political acrobatics’

In the early 1980s it was Rawlings’ political acrobatics that took one’s breath away. He was the radical leader whose ministers had convinced a sceptical population that a hundredfold devaluation of the national currency, the sacking of half the civil servants, and the sale of most state-owned enterprises to foreigners was an act of sacrifice and patriotism. Without question, it was an act of political daring.

From a pro-Havana approach, Accra was now a lode-star for capitalist development. Its economic reforms were held up as positive proof that the Washington consensus policies of the Fund and the Bank delivered high growth and foreign investment. Social well-being and jobs proved more elusive.

But daily reality tells a different tale. Recalcitrant Bank officials concede they misjudged their policies: the tens of thousands of highly qualified civil servants made redundant would not find jobs in Ghana’s narrow and under-capitalised private sector. Instead, they migrated to Europe and North America where many took senior posts in government and business.

Those local companies trying to diversify and source locally were submerged by the Bretton Woods’ wave of trade liberalisation. Local economists say that more of Ghana’s economy fell into foreign hands than under Britain’s colonial rule.

And then in came the political tide in the wake of the crashing down of the Berlin Wall when Rawlings and his allies succumbed to local and international pressure to open the system to multi-party politics. Adieu, no-party politics.

‘Rawlings, the deliverer of market-economics’

Given to stopping his convoy to join with work gangs unblocking drains or repairing broken water pipes, Rawlings’ populism made him an instinctive election campaigner.

By then, western powers such as the US and Britain and erstwhile of the People’s republic had swung behind Rawlings the deliverer of market-economics and an ostensibly pluralistic politics. He had launched the National Democratic Congress in 1991 to the delight of his base which was now stronger in the rural hinterland.

Some of his party allies were less sure-footed. So the NDC didn’t take any chances and blatantly rigged the 1992 elections, and less blatantly, the 1996 election.

Such manoeuvres occasioned only the mildest rebukes from overseas. By then, western powers had swung fully behind Rawlings the deliverer of market-economics and ostensibly pluralistic politics.

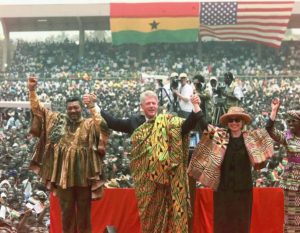

US President Bill Clinton’s and his wife Hillary’s state visit to Ghana in 1998 hosted by Rawlings and his wife Nana Konadu, was expertly choreographed for their mutual political advantage.

In 2000 Rawlings quit with better grace than many had confidently predicted. His anointed dauphin, academic and tax expert John Atta Mills lost the elections, leaving Rawlings to hand over to an Ashanti aristocrat John Agyekum Kufuor at the helm of a centre-right New Patriotic Party government.

One of Ghana’s more curious political liaisons in recent years has been the close relationship between Rawlings, his wife Nana Konadu and President Nana Addo Akufo Addo, who took the NPP back to national power in 2016.

This closeness was clear last week when President Akufo Addo announced a suspension of election campaigning for a week and the organisation of a state funeral for Rawlings, in close cooperation with the family.

Legacy left behind

Those obsequies will be held against the backdrop of a closely fought national election campaign where one of the key debating points will be grand corruption, an issue which had propelled Rawlings to leadership 40 years earlier.

Arguments over Rawlings’ role will not quieten in the weeks ahead. Many of those workers and farmers and their families whose hopes of a voice in politics and economic improvement were vested in the Rawlings era have stayed dutiful supporters despite continuing hardship.

It is the bankers, commercants and commission agents who remain some of Rawlings’ harshest critics although they finally benefited most from the IMF adjustment theology and political stabilisation. And for those still seeking the radical social change that the 1979 revolution had promised, aluta continua.

Rawlings’ surviving family includes his wife Nana Konadu Rawlings, three daughters, Zanetor, Yaa Asantewaa and Amina, and son, Kimathi. His mother, Victoria Abouti, died just two months ago at the age of 101.

By Patrick Smith