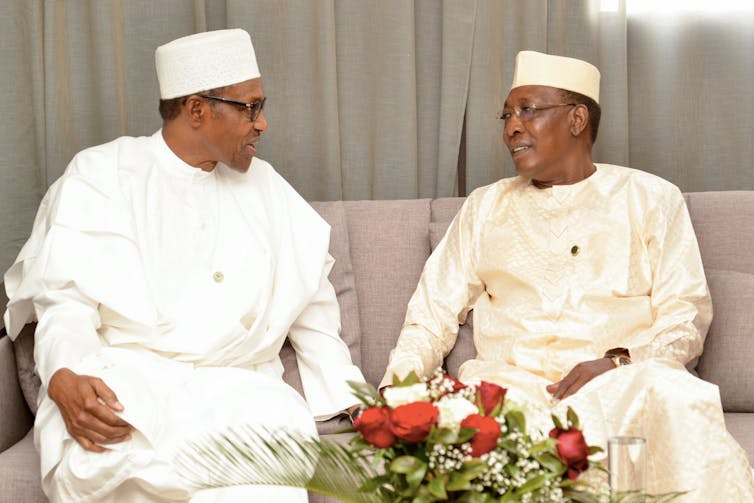

Brahim Adji/AFP via Getty Images

Folahanmi Aina, King’s College London

The death of Chad’s President Idriss Dèby has inevitably alarmed foreign and national security policymakers in Nigeria, the West African region and as far as France.

The 68-year-old Dèby was killed on the frontline in northern Chad across the border with Libya where Chadian troops have been battling the foreign-backed rebel group Front pour I’Alternance et al Concorde au Tchad.

A transitional military council headed by Dèby’s son, Mahamat Dèby, has since taken over the reins of power.

Dèby had been in power since 1990 and had recently declared victory in elections that gave him his sixth term in office. The official result said he had garnered nearly 80% of the vote. The poll was boycotted by the opposition, and fell short of qualifying as a free and fair election.

But his sudden death has serious implications for regional stability and the war against insurgency in the troubled Lake Chad Basin and the broader Sahel region in West Africa.

It is also being keenly felt by two countries that play significant roles in the region – Nigeria and France.

For Nigeria, the dangers posed by Dèby’s death are very close to home. This is primarily because of the potential proliferation of weapons into its borders from Libya, via Chad and possible collaborations between violent extremist groups and rebels.

As the region and the rest of the world looks to Nigeria, Abuja owes it to Nigerians, as well as countries in the Sahel, to take a leading role in ensuring instability doesn’t spread. But to do so it needs to act immediately and decisively. Time is of the essence.

Uncertainty

Dèby was a close ally of Nigeria, the region’s sole hegemon.

Under his rule, Chad contributed significantly to regional efforts through the Multinational Joint Task Force aimed at defeating Boko Haram and its breakaway faction, the Islamic State in the West African Province (ISWAP). Chad also committed 1,000 troops to the Sahel region.

The fear is that Dèby’s death could affect Chad’s future commitments. If this happened, Nigeria’s ability to prosecute the ongoing war – domestically and across the Lake Chad Basin area – would be compromised.

Nigeria’s Defence Minister, retired Major General Bashir Magashi, has already expressed concerns, warning that if there was insecurity in Chad there would “be a lot of problems.”

With the largest armed forces in the region, the stakes are high for Nigeria. Not only is it engaged in fighting insurgencies in the Lake Chad Basin region, it is also grappling with its own internal security challenges.

These range from the threat posed by Boko Haram and Islamic State in West Africa Province, in its North East region to armed banditry across the North West and North Central regions.

There is also an emerging threat in the South East by the proscribed Indigenous People of Biafra. And there are potential spill overs of the farmer-herder clashes in the North which have the potential to further complicate the spate of kidnappings across the South West region.

Another state actor with significant interests in the region that has lost a staunch ally is France. Paris provided Dèby with solid backing during his 30 year rule.

France was quick to demonstrate its willingness to support and work with the military leaders who have assumed power.

This, in turn, raises questions about the country’s commitment to the rule of law and democracy in the region. This also has consequences for the continued support of other world powers who have kept a keen interest on developments in the region such as the European Union and the US, who may be a bit reluctant to work with Chad’s unconstitutional military junta.

An issue of concern with dire consequences is the fact that Dèby was killed by rebels, who are non-state actors. This could potentially embolden other dissidents and terrorist groups who thrive on exploiting local grievances. Their efforts are invariably met by intensified efforts at enforcing peace and security by states in the region.

The problem with this is that it could further reinforce an already militaristic approach to regional stability, at the expense of non-militaristic approaches such as socio-economic and political factors.

What next

The timing of his death poses significant challenges for security forces. Troops across the region already have their hands full assisting with enforcing lockdown measures while the activities of extremist groups continue unabated.

There’s also a danger that some ISIS-affiliated violent extremist groups could seize the moment to intensify their activities across the Sahel region. They may also capitalise on his death to seek expansion through renewed recruitment and disinformation on social media.

Despite these uncertainties and concerns, Nigeria has a role to play in stepping up to the plate to provide the region with the leadership it needs at this time.

Nigeria’s leadership in the region in the past has been crucial to state survival as well as regional peace, security and stability. Nigeria for example led the Economic Community of West African States’ Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) interventions in Sierra Leone and Liberia.

With the vacuum created in the region following the death of Dèby, Nigeria must act decisively now more than ever, to promote regional peace, security and stability.

To do this efficiently and effectively, Nigeria must expend its diplomatic and political capital in mobilising key regional partners. Dispatching a Special Envoy to the Lake Chad Basin and Sahel regions would be a first step. It must also provide renewed reassurances of its continued commitment to security cooperation with the Multinational Joint Task Force and other West African states.

It’s much needed leadership efforts must also reflect the mutually linked security concerns of the states in the region and their societies for it to stand the test of time. Hesitation on the part of Nigeria will have dire consequences for its own internal peace. It will also have a negative domino effect across the broader region.![]()

Folahanmi Aina, Doctoral Candidate in Leadership Studies, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.