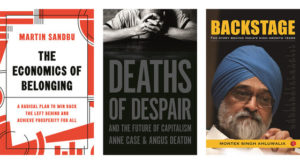

July 14, 2020//-Montek Singh Ahluwalia provides an invaluable insider’s account of the making of India’s economic policy between 1979, when he returned to his home country from the World Bank, where we worked briefly together and became good friends, and 2014. It is the story of a substantial success.

Ahluwalia was sure that the aim in a country as poor as India had to be high economic growth. This, in turn, required economic liberalization, supported by pragmatic institutional reform.

The book details how the balance of payments crisis of 1991 made this possible. The book gives due justice for seizing this opportunity to the prime minister, Narasimha Rao, one of India’s most underestimated politicians.

But the hero is former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, with whom Ahluwalia worked closely throughout. Ahluwalia himself provided the needed plan in 1990 with the “M Document,” which “presented an integrated strategy for reform—of fiscal policy, industrial policy, trade policy, and exchange rate policy.” You can check here information about Indian businesses.

Beyond question, these reforms shifted India onto a higher growth path. This became even more evident in the first decade of the new millennium, when Ahluwalia joined the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government as deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, under Prime Minister Singh, between 2004 and 2014.

As he states, “The first seven years [of the UPA government] recorded a growth rate of 8.5 percent. Indicators such as export growth, private investment, and reduction in poverty also showed excellent performance.”

Yet the book also raises important questions. Here are just three.

First, as Ahluwalia notes of the 1990s, “The approach to change was a combination of gradualism and what I have called ‘reform by stealth.’ Why were politicians, notably the Congress Party, never willing to make the success of these reforms and the need to take them further the center of their political platform?”

Second, why has growth decelerated? Two complementary explanations emerge from the book. One is that the growth was in part a result of an unsustainable credit boom in the private sector. That left a legacy of bankrupt companies and weakened financial institutions—the “twin-balance-sheet problem.”

Another is that the initial reforms, predominantly liberalization following the dismantling of the “License Raj,” had by then done all they could do. India needed second-generation reforms, notably of its institutions. But, as Ahluwalia writes, “we did not pay enough attention to the need to build institutions that would promote good governance.”

Finally, what happens next? Ahluwalia describes the economic record of the six years of Narendra Modi’s National Democratic Alliance government as “beginning with a bang and ending with a whimper.”

The government has achievements to its credit. But it has done undesirable things (notably demonetization) and not done desirable things (notably resolving the debt problem). India’s economic future was quite uncertain, even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet Ahluwalia himself was an optimist when he returned to India in 1979. He was also an optimist throughout his career. He is, he concludes, still today “an unrelenting optimist that…the India story of high growth and development will…continue.” We must hope he is right.